Jazz Clarinet

By BOB BERNOTAS

When you hear the phrase, “New Orleans jazz,” what three instruments immediately come to mid? That’s right: cornet, trombone, and clarinet. In those early jazz combos, the clarinet provided a soaring, high register obbligato that enhanced, and, in the hands of the amazing Sidney Bechet, challenged, the cornet’s lead line. A decade or so later, the clarinet occupied a rightful place as one of the signature instruments of the big band era, serving as a distinctive tone color in the ensemble and an important solo voice. After all, the so-called “King of Swing,” Benny Goodman, was a clarinetist.

But starting with the bebop era, the clarinet inexplicably began to fall out of fashion in jazz. Despite the persistence of such gifted boppers as Buddy De Franco and Jimmy Hamilton, by the end of the 1950s the instrument had all but disappeared from the music’s mainstream. None of the important small bands of the day, and, with the exception of Duke Ellington, very few big bands, featured a clarinetist. As a consequence, few pure clarinet players – as opposed to saxophonist doublers – came to prominence in jazz in the post-war period.

Today, many (perhaps most) jazz listeners regard the clarinet as a relic of the past, the property of moldy figs and swing-era diehards. Nevertheless, though the 1960s and 1970s the avant-gardists, in their quest for new sounds (as well as old ones), rediscovered the instrument, at least in a limited way. Some even began to feature members of its extended family, like the alto, bass, and contrabass varieties, occasionally in multi-clarinet ensembles. And during recent decades, this music has been enriched by a handful of dedicated clarinet specialists, like the late John Carter, Alvin Batiste, and Don Byron, who have fought to keep their instrument in the forefront of creative jazz.

Sidney Bechet: The Best of Sidney Bechet (Blue Note, 1994; original recordings, 1939–1953)

This New Orleans-born master dominated every ensemble he ever played in with his florid, vibrato-driven bravura. Among its treasures, this collection includes two genuine jazz masterpieces: Bechet’s soulful clarinet blues, “Blue Horizon,” and “Summertime,” featuring his inimitable soprano saxophone.

Jimmie Noone: An Introduction to Jimmie Noone: His Best Recordings, 1923–1940 (Best of Jazz,1997)

Originally a New Orleans contemporary of Bechet, Noone made his mark in Chicago as both a blues specialist and a singular interpreter of such popular tunes as “I Know That You Know” and his lovely theme song, “Sweet Lorraine.” He also was an early and important influence on the young Benny Goodman.

Barney Bigard: Barney Bigard Story, 1929–1945 (EPM,1996)

Bigard brought the New Orleans Creole clarinet tradition into Duke Ellington’s orchestra, where, from 1928 to 1942, his fleet solos and intricate embellishments lent color and character to countless jazz classics. His long post-Ellington career included a stint with Louis Armstrong’s All-Stars (1946–55).

Benny Goodman: Complete RCA Victor Small Group Master Takes (Definitive,2000; original recordings, 1935–1939)

Although his big band defined the Swing Era for millions of fans, over the years Goodman played his best jazz with his various all-star small groups. This two-CD set spotlights BG’s original trio (with pianist Teddy Wilson and drummer Gene Krupa) and quartet (which added Lionel Hampton on vibes).

Buddy De Franco: Mr. Clarinet (Verve,1953)

De Franco emerged from mid-1940s big band reed sections (notably that of Tommy Dorsey) to become the essential bebop clarinetist. This typically brilliant session features his stellar working quartet of the day with pianist Kenny Drew, bassist Milt Hinton, and drummer Art Blakey.

Jimmy Hamilton: Can’t Help Swingin’ (Prestige,1961)

For 25 years (1943–1968) this technically superior musician served as Duke Ellington’s principal clarinet soloist. Hamilton plays both clarinet and his Ben Webster-inspired tenor saxophone on these tracks, which also feature two all-time jazz giants, trumpeter Clark Terry and pianist Tommy Flanagan.

Eric Dolphy: Out There (New Jazz/OJC,1960)

More than anyone else, this visionary multi-reedplayer established the bass clarinet as a jazz instrument. On this pianoless quartet date with Ron Carter on cello, Dolphy is heard on bass (“Serene” and “The Baron”) and B-flat clarinets (Charles Mingus’ “Eclipse”), as well as flute and alto saxophone.

John Carter: Castles of Ghana (Grammavision,1986)

A gifted instrumentalist and an important composer, Carter helped carve a niche for the clarinet in the jazz avant-garde. This recording, the second movement of his monumental five-part epic Roots and Folklore: Episodes in the Development of American Folk Music , is regarded by many as Carter’s finest work.

Clarinet Summit (Alvin Batiste, John Carter, Jimmy Hamilton, David Murray): In Concert at the Public Theater (India Navigation,1981)

Formed by John Carter, this quartet united three hardcore modernists – Carter, Batiste (who lives and works in New Orleans), and Murray (on bass clarinet) – with respected veteran Hamilton. Their now legendary debut concert offered a wide-ranging repertoire of Ellingtonia, bebop, and free playing.

Hamiet Bluiett: The Clarinet Family (Black Saint,1984)

This eight-clarinet ensemble (plus bass and drums) truly encompasses the instrument’s entire family, from the tiny E-flat sopranino to the large contrabass. This one-time-only live performance features Bluiett on alto clarinet, along with such accomplished clarinetists as Buddy Collette, Don Byron, and J.D. Parran.

Don Byron: Music for Six Musicians (Nonesuch,1995)

Committed to bringing the clarinet back into the forefront of creative jazz, Byron respects no musical boundaries. His creed is, “If it can be played, it can be played on the clarinet” – swing, klezmer, lieder, show tunes, funk, or, on this sextet session, skronky, Afro-Cuban-inspired original compositions.

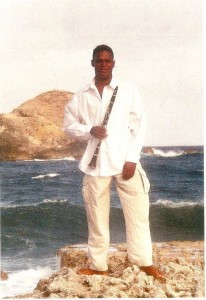

Paquito D’Rivera: The Clarinetist: Vol. 1 (Music Haus,2001)

On this rare all-clarinet recording, the Cuban-born reed virtuoso performs with a chamber orchestra and a Latin jazz rhythm section, and in trio with piano and cello. D’Rivera skillfully bridges the gap between classical and jazz, with a healthy helping of tango á la Astor Piazzola mixed in.

Related Posts

Tags: clarinet, clarinet and saxophone, clarinet music, how to play the clarinet, learn to play the clarinet