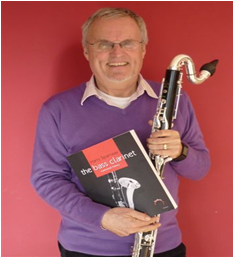

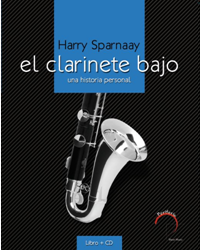

The bass clarinet – A personal history

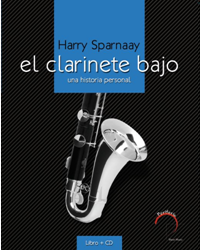

El Clarinete bajo – una historia personal

Published by Periferiamusic -Barcelona

www.periferiamusic.com

The Bass Clarinet – a personal history Book and CD

ISBN: 978-84-938845-0-5 / Price: 69 EUR

El Clarinete bajo – una historia personal, Libro y CD

ISBN: 978-84-938845-1-2 / Precio: 69 Euro

Excerpts from the book

page 7 – Table of Contents

page 14 – Chapter 3: From the very beginning until now

page 31 – Chapter 4: Concise history of the bass clarinet

page 57 – Chapter 6: Range

Part 6b:The high notes

page 138 – Chapter 8: Special techniques/effects

Part 8n: Multiphonics

page 143 – Chapter 8: Special techniques/effects

Part 8n: Multiphonics

page 248 – Chapter 15: Biography

Comments, Critics and Reviews

Ana Lara – composer / Mexico

I’ve always admired Harry Sparnaay.

First of all because he has convinced everyone that the bass clarinet is a great instrument capable of doing everything imaginable and unimaginable and has created a very extensive repertoire. And then also because he formed a new generation of not only virtuosi, but also of great bass clarinettists.

He is the great master of the bass clarinet.

Everything about the instrument he knows and is using all his sound possibilities with an immense enthusiasm.

All he needed to do was writing the long-awaited book on his instrument and he did so.

And the book is wonderful, funny and profound. All you have to know about the instrument is included, written with the same lightness and depth it’s author has. Many examples, many stories but mostly this book is him, with his charm, intelligence and talent.

This is a must for music lovers and musicians (performers and composers).

Harry Sparnaay has the great talent to combine his personal experiences (not without humor) with essential information for those who want to write for or to play the bass clarinet.

Thanks Harry for this book. The title says it all, it is a reflection of the passion for your instrument, music and life, a life you have spent to share with us the beauty and power of the bass clarinet.

Thank you so much for this great gift you gave to us all.

Luiz Rocha – bass clarinettist / Brasil

I have been fortunate to read your book already, I bought the first edition in English.

I loved the quality of your book, the depth of the technical part and the personal tone of the narrative. Many congratulations.

Ernesto Molinari – bass clarinettist / Switzerland

Your book arrived a few weeks ago and I wanted to tell you how much I enjoyed reading it. It is not only informative but entertaining as well! Your passionate journey and your quest to fathom new worlds of sounds, notations and techniques has inspired clarinetists and bass clarinetists (including myself!) and continues to do so. I wish there had been a book like yours while I was beginning my own quest over twenty years ago. I will recommend your book to all of my students and introduce it in my master classes in Darmstadt and Graz because it is a genuine personal history of the bass clarinet journey still under way. Thank you for taking the time and effort to write a book while still continuing a full concert and teaching schedule and for sharing your experiences, your discoveries and your passion for music!

Congratulations, Harry!!!

David Bennett Thomas – composer / USA

I just finished your amazing book. I can’t imagine a more informative

and helpful book for anyone wanting to play or compose for the bass

clarinet. I read all of the text on the train, and finally had a minute

to listen through the musical examples. I’m so glad I did! It

was amazing to hear those sounds. There were some effects that I

didn’t even know were possible. The book is very well written, in an

enjoyable and sometimes humorous style. Who would have thought that a

book about the bass clarinet would be such a page-turner!

Now if we can just get someone to write a similar book for every other

instrument to help those wanting to compose.

Sungji Hong – composer / Korea

A vast amount of experience is collected within this book, where we find a wide range of extended techniques explained with diverse examples of contemporary music.

It leads us into the musical journey of Harry Sparnaay, whose career is a true history of contemporary bass clarinet music.

‘The Bass Clarinet’ by Harry Sparnaay will certainly be an inspiration for all clarinettists and composers who are seeking for a deep knowledge of the instrument.

Oğuz Büyükberber – bass clarinettist / Turkey

I remember the day my uncle brought a student model bass clarinet for me from Paris. It was the first bass clarinet I had ever seen in my whole life until then! In Turkey, it was so hard to have access to the right material in those days: Instruments, recordings, books… I was so lucky to travel all the way to study with you personally. But this book you wrote gives the possibility to musicians from all over the world to enjoy and benefit from your incredible knowledge, unprecedented experience and great personality. The high standard you set for this lovely instrument that I have so much passion for will only be clearer and better understood as a result of this book.

Thank you so much!

Jane O’Leary – composer / Ireland

A great reference book when writing my next piece for bass clarinet! It is a

wonderful achievement-congratulations. With a life as full and rich as

yours, it’s so important to have it recorded in this way. Great fun to read

and hear all your stories. It feels like having a conversation/meeting with you when reading it….very nice!

It’s lovely!

Hugo Queirós – bass clarinettist / Portugal

Thank you very much for writing your book. So easy and so exciting, for me it has been a pleasure to read and follow the great adventure that was your life with the bass clarinet!

Thank you for sharing so much valuable information and I hope you will continue sharing so much knowledge that you have about this noble instrument…

During your live you inspired great musicians and composers and with this book you will reach much more…

Congratulations for this masterpiece!

Daniel Schröder – (bass) clarinettist / Germany

I really enjoyed that your book is written from such a personal point of view. It is so much nicer to read if you got an impression what a special subject means to the person who is telling you about it. Then it is like a story that is told and you like to listen to.

Al Wegener – composer-bass clarinettist / USA

It is a great book … like all your reviewers say. And I have found it very useful for my bass clarinet composing and performance. The book cost me $135 U.S. dollars. That, here in the U.S. and now, is just a lot of money but the book is well worth. Perhaps a good idea to put up some selected pages from the book on your web site to give folks a taste, perhaps including some audio too? Buying the book blind this will make sales easier.

Thanks for everything you do for the bass clarinet!

Roderik de Man – composer / the Netherlands

“Maybe the bass clarinet has been waiting all these years for Harry Sparnaay” wrote William Littler (Toronto Star) in the seventies.

We may now add: This certainly is the book bass clarinettists and composers have been waiting for all these years.

The book is a real gem!!!

Sarah Watts – bass clarinettist / England

When you would expect that as it is Harry Sparnaay writing a book it will be absolutely full of contemporary music and nothing else, than you will be really pleasantly surprised that it is so much more. It isn’t just a personal history; it covers everything about the bass clarinet.

Harry Sparnaay – a personal history, is really a must for everyone who wants to know more about the bass clarinet. It is a huge wealth of information from the history of the instrument to information on general techniques, contemporary techniques and repertoire. Also it is full of information about other players and I like the way that contact details are included for many players from around the world and products associated with the instrument. It is written from the heart with much affection and humor.

Luc Lee – bass clarinettist / Taiwan

This book is bass clarinetist’s gift!!

It includes so much bass clarinet information.

Let me learn more about bass clarinet. I enjoyed it very~~~ very much!!

I love this book.

Bravo!! Bravo!!!!

Sergio Blardony – Sulponticello, Revista on-line de música y arte sonora / Spain

Periferia Sheet Music surprises the music world with this book by the bass clarinettist Harry Sparnaay, that, far from being limited to mere theoretical and technical treatise, introduces the composer, performer and musician in general, to the world of his instrument from a personal and analytical point of view. It is a very well presented edition that includes a CD with multiple examples of the techniques discussed.

To write a review about a theoretical treatise on an instrument (if that is indeed what we can call this book!) can tend to be complex and often be boring for the reader. However, the present case, the Periphery Sheet Music edition of “The Bass clarinet”, bass clarinetist Harry Sparnaay, dispels these fears from the very first page. Firstly, it is observed from the very beginning that this is a personal approach, living up to the caption that accompanies it (“a personal history”). Secondly, the author (without doubt, one of the most important players of the bass clarinet) has managed to reconcile, on the one hand, extreme seriousness and technical rigor with irony and a frequent sense of humor, which makes the reading quite agreeable, on the other hand. This is something highly unusual in a book of this kind. These factors give to the written text something which, as I shall try to convey in this article, makes this editorial proposal both atypical and quite valuable. It is definitely a book addressed equally to performers and to composers, but the later will always be indebted to it. I will try to delve into why this is observed to be so, and precisely from the composer’s perspective, about which I am able to speak from experience.

Usually, when faced with an instrumental treatise, the composer’s main concern is, and in this order, 1) if it deals with the extended or contemporary techniques (something which that is generally not rare in any text of this kind) in case our own language proficiency is limited, 2) in which language is written and if it is “readable” (this generally is not considered a major problem); and finally 3), the abundance of tables and examples of the techniques (one is always on the hunt for a good table multiphonics …). If the text meets these needs, and does it well, it will be eligible to sit on the shelf of reference books in instrumentation. However, time and experience tells us that many treaties, for various reasons are not as useful as they might seem at first sight. In many cases, it is not so much that they contain incorrect or inaccurate information (of which there is generally a bit of that), but that over time the current techniques become a bit moldy or out of date. It is not uncommon to find that a multiphonics example cannot be realized due to small changes in the instruments or in the reeds, that are no longer used as commonly as in the time the books were written. These aspects are of great importance for the composer, as an inadequate organization of multiphonic examples in a publication can mislead the composer into believing in a deceiving kind of soundscape where practically everything that appears in a table can be done exactly as the book says. We must also bear in mind that many of these books have been made in research settings in which the starting point was “possible” rather than “reason”, primarily because the motive was to study the physical and acoustic potentials of the instrument, rather than from the perspective of genuine usefulness for the composer (in these cases, good judgment and experience are to be expected of the composer, since there is no reason to limit a comprehensive technical or investigative text out of concern for the composer’s lack of understanding about the instrument).

The Bass Clarinet emerges from a completely different point of view than that of a purely investigative text or compilation of material. It emerges from the perspective of being a useful book for composing precisely because it warns the creative mind of the illusions, very precisely setting limits on those techniques and aspects of the instrument that may be conflictive. One could argue that this route is dangerous or limiting because it tends to restrain the impulse to create and explore freely on the instrument, but nothing is further from the truth. Sparnaay makes it clear that almost anything is possible on the instrument, and what is not possible, can be generally be achieved with work and inquiry. This may be. However, the concept of “almost anything is possible” should be taken into careful consideration, because it is not productive to expected-limited possibilities from the instrument, or to cultivate an excessive confidence in the capabilities of the player to solve these challenges. Because the composer then falls into the trap of trespassing the very real technical impossibilities of the instrument.

From this perspective, I can cite a number of passages that clearly illustrate the focus of the book. For example, Mr. Sparnaay says of trills, tremolos and bisbigliando: “In general, playing trills does not pose major problems for us, but a trill c to c sharp in the low register is-on almost all bass clarinets-almost impossible”. Another example about the quarter-tone: “Also playing a phrase in an insanely high tempo, flying over three octaves, fortissimo and ‘Flatterzunge’, and full of quarter tones is meaningless. The result will be a terrible roar hawking without any discernible pitch. It looks nice and well thought-out, but it does not function at all! ” Or on multiphonics:” There are completely written out books with multiphonics which may give the impression to composers that actually all the notes sound clearly notated and equally and that you as composer can just go ahead. However this is a fallacy and seems to be misleading for many composers.” These quotes make clear the points about the book that I have tried to expose and explain, and the importance of a book like Sparnaay’s for realizing a logical and effective manner of writing for the instrument.

In addition to these aspects, perhaps the most relevant from a practical point of view, including the important collection of samples and examples contained on the CD that accompanies the book, and as I mention at the beginning of this article, is the particularly pleasing style in which the book is written. We feel as if we are privy to a very personal musical experience, and this implies the risk of coming across at times as excessive But Sparnaay dispels this through an effective combination of the essential objectives of the text. In other words, it is both completely original and personal and, at the same time equally effective from a “technical” point of view, all the time not coming across as labored or contrived. In this sense, it comes across as seamless in a very satisfactory way.

In regards to the organization of the book by chapter: in addition to a significant amount of text devoted to forms of notation, instrumental ranges, extended techniques, use of the instrument in an electro-acoustic context, etc., we also find chapters which are to be considered less common and which result very interesting and entertaining. From the “Personal introduction” and “From the very beginning until now”, to a journey through the history of the latest music, going all the way to a chapter devoted to programming of works for bass clarinet, there is even a section dedicated to stories and anecdotes that will give the reader a good laugh. On the practical level are the sections dedicated to repertory, publishers and music information centers, or to composers who have written works for the instrument, with various references to them, including the web.

In short, this is an essential book on the bass clarinet for the composer or performer, but it is also highly recommended to other music professionals who can find in this text transversal aspects which, above all, offer the occasion for reflection on ideas that transcend the specific study of an instrument.

Núria Giménez Comas – composer / Spain

For me it was the discovery of a fascinating personal history closely tied to development and sound research for an instrument that is (thanks to the dedication) very rich in possibilities. Consequently I think it is a practical tool for composers and performers through numerous examples and comments, resulting out of a huge experience in the field, making it a very important tool, we could say an obligatory one. I’m using the book very often now, it is very clear and practical!

Thanks Harry!

Marij van Gorkom – bass clarinettist / the Netherlands

I have read your book several times and enjoyed it very much. I find it very personal and very recognizable.

I dreaded a little bit to go through a multiphonics chart again, since it usually takes ages and ages because not everything works etc.

But it only took me a quarter of an hour!

Great and really wonderful to have a chart which you can just pass on with the message that it really works and also for me as a Selmer player.

Without doubt it’s clear to me that I will strongly recommend this book to every composer.

So, thanks again and again.

Jacobo Durán Loriga – composer / Spain

Books on instrumental techniques can be very dry and boring. Lucky are they who are interested in the bass clarinet, because with “The bass clarinet” by Harry Sparnaay they have a book which is comprehensive and entertaining as well. On almost every page there’s a reason to smile, or laugh even, for example when he lists various remote regions of the globe that are ideal for studying the very high notes that can usually cause problems with family and neighbors.

The advice given to composers and musicians is priceless. Advices based on experience, not just on theory. It is the strength that comes from knowing what you are talking about and to argue from practical experience. With his guidance composers will know what can be done and how, and what best to be avoided, the way to use notation with advantages and disadvantages explained. All documented with photos, sheet music, fingering chards and a CD.

There is only one thing that would surpass this book. To have the author at your side to be consulted at any time, although I suspect that he would sometimes use his own book to have the most complete and reliable reference.

Petra Stump/Heinz-Peter Linshalm – bass clarinettists / Austria

We received your book about a week ago and read all the chapters by now.

It is not only a comprehensive encyclopaedia about the bass clarinet and its techniques but also an inspiring story of a life dedicated to the bass clarinet. Complete in every respect!!! Thank you for all your efforts!!!

Laura Carmichael – bass clarinettist / USA

You have written a superb book, with comprehensive examples, fingering charts, repertoire lists and stories of his forty-plus years of work with the bass clarinet. What stands out the most to me is the way your personal voice is heard throughout; the reader is exposed to the various sides of you: demanding and focused, funny and self-deprecating, energetic and sharp. Your stories, opinions (often dosed out with humour), and way of living with the bass clarinet are interwoven with a plethora of technical information. You let the reader in on your personal perspective, your thinking, motivations and drive. I cannot think of another clarinet book which achieves this combination of practical information with such a compelling informal voice. In the section about notation, “The Confusing Notation” and “The Really Bad Notation” I had to laugh out loud. The book is a rich resource, definitely a must have reference for bass clarinettists and composers, and no doubt useful to anyone interested in the development of the bass clarinet as a contemporary music solo instrument over the last forty years.

Montse Martínez Gracía – Consultant Feng Shui Traditional / Spain

What fantastic reviews and comments your book received!

Surely the fundamental value of the work is YOU, your personality and LOVE, in capital letters, your feelings for the music and your instrument.

This love is in everything you say when you speak about them, or during teaching or through anecdotes and it is certainly reflected and transmitted through reading your book.

Hence it isn’t an other music book . . . it is something different and very special.

Josep Barcons Palau – Revista Musical Catalana – / Spain

It is no exaggeration to say that Sparnaay has opened Pandora’s Box of the bass clarinet, giving the instrument a privileged place in the music of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, thus redeeming it from the secondary role it was sentenced to in the orchestras. This Pandora’s Box is now presented in a book that is like a Bible of the bass clarinet.

Like the Bible, consisting of several books, Sparnaay’s book contains several books in one: a technical book indispensable for both composers and instrumentalists (covering everything from the reeds to the notation of multiphonics), a history book, a catalogue of compositions, a collection of special effects and examples (with a CD attached), a multimedia reference source, and an autobiography.

The novel approach of the book is that even though the paragraphs and chapters are fully indexed and sorted, the contents know no boundaries and circulate freely from the beginning until the end.

The text is like a sponge, having absorbed the lively, provocative and humorous style of the author; in the midst of a technical explanation, anecdotes and personal assessments appear.

This book is suggested for anyone who wants to approach the world of contemporary music, the bass clarinet, or musical culture in general.

Sparnaay’s book crosses the same borders that the bass clarinet itself has crossed. He is the most authoritative voice on the art and history of bass clarinet, and now the fact that he has written about the instrument has become a significant historical event itself.

Ilse van de Kasteelen – singer-composer / the Netherlands

I have spent the past days with your book. BRAVO, what a wealth of information, what an adventure. And written as you are, driven and with a great sense of humor. Many people here will, like me, learn a lot from it. It is a privilege to be included.

Ainhoa Miranda – bass clarinettist / Spain

Not only seeing all what you have done for this amazing instrument but also to read all your experiences adds joy and fun to play it.

You make playing not difficult but interesting. Any new challenge becomes a trip through the sound and possibilities of an instrument that thanks to you is admired.

I am so happy for you writing this book!

A book that makes the bass clarinet to be alive

Gérard Pape – composer / France

How nice to find a book on the bass clarinet that does not

forget that there is a person behind the instrument! Not only the history of the instrument but also that of the instrumentalist! That your book is a “personal” history means a lot for me as it makes your advice to young instrumentalists to play with their soul, to find a sound that comes from who they are all the more important!! While your book is very helpful as to what is possible or

not on the instrument, you admit that the impossible does exist!

While you have found and describe many wonderful possibilities for the instrument, you also tell that certain things are really not so possible which is also quite honest and helpful!

So, I come to the conclusion thanks to your book that writing for an instrument should also include a phase of testing one’s ideas with the player. Research in music is a real collaboration between player and composer. Your book is an invaluable report on many years of research and collaboration with composers.

Best wishes and thanks.

Stephan Vermeersch – bass clarinettist / Belgium

I have been enjoying your book for the last two weeks; a must for every bass clarinettist and composer who wants to write for this beautiful instrument.

I cannot think of any item that is not included, the recordings also are straightforward: no tricks.

Thank you very much for this beautiful work!

Jaap Bosman – bass clarinettist / the Netherlands

I immediately copied the support strap Harry describes in chapter 7, “Playing position”. In this way the book paid itself. The strap is really great, much more comfortable than all the other ones. The bass clarinet literature list is the solution for the lonely bass clarinettist searching for new pieces. Everything you cannot find on the net is in the book, and the personal way of writing makes it an enjoyable book to read and use.

Didier MASSIAT – Copyright Department, Gérard Billaudot Editeur SA / France

I have just received your book, and all I could say can be summed up: congratulations for such a work!

The result is really marvellous.

Jetle Althuis – bass clarinettist / the Netherlands

The book is grand in many respects: it presents a good overview of not only the possibilities- but also the impossibilities of the bass clarinet. (For me as bass clarinettist is comforting to see some things are just not possible).

Here someone speaks with not only a wealth of knowledge and experience, the passion for the bass clarinets radiates from every passage you read.

On every page you sense the bass clarinet holds no secrets for Harry Sparnaay. To me it is most remarkable the book reads as if the writer is speaking directly to you.

Harry Sparnaay is speaking!

This book is a must have for every (bass) clarinettist and is strongly recommended to composers.

Hans Joachim Hespos – composer / Germany

Many thanks for the wonderful book, the compendium of your life’s work

– you and your instrument -. It will be a standard work for many young musicians.

Many congratulations!

Gabriel Brnčić – composer / Spain

An excellent book. Amongst so many absurd and badly composed books this truly is a breath of fresh air. Many congratulations to you and your co-workers.

Anton Willems – bass clarinettist / the Netherlands

Congratulations on your beautiful book. I have it and I’m still reading it with great pleasure. It is an inspiring book, especially because it has a relaxed and often humorous personal style (I think so, but so your lessons often were), but really to the point regarding the possibilities and impossibilities, and everything is told with passion. The CD sounds very beautiful and natural in terms of sound. For me it is a very valuable addition to the bass clarinet literature. Often these books are quite business like and dry thus boring to read. It really surprised me.

I hope the book finds its way to the musicians well.

Frans Moussault – bass clarinettist / the Netherlands

I adore your book. The best thing I bought over the last years.

When I read it I hear you talking. The next week I’ll go through it and study the

standard techniques in the book and they will undoubtedly inspire me.

I am a proud disciple of the writer.

Sarah Watts – HARRY SPARNAAY INTERVIEW FOR CASSGB (Clarinet & Saxophone Society of Great Britain – www.cassgb.org)

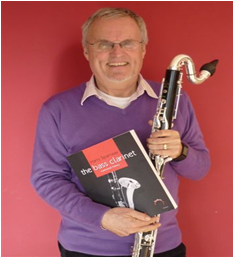

In May I went to see Harry Sparnaay perform a concert in Barcelona and also to interview him about my research on multiphonics. During my trip I also made time to talk to Harry about his new book ‘Harry Sparnaay, the bass clarinet – a personal history’.

SW: My first question to you is why did you decide to write this book?

HS: Why did I write it? Well first of all I have to be honest already years ago they asked me to do something and I said no. Now this is very interesting – it has nothing to do with music. I have one problem. When I have to do something in my house or something else I make a list. And I love to do this! So I make a list and when I have finished everything on the list … the satisfaction!! And that is the mistake of what I did!! Two years ago Roderik de Man (the composer) asked me and said you have to do it! I said no. The next day I was sitting at the computer and I made a list of what I thought had to be included in the book. And that was the mistake! The next day I was speaking with my wife about something and I said wait a moment and I went to the computer – that was a mistake and from that moment on it was nearly every day and of course I have so many things that have happened, so many pieces written. So first I wrote what came in my mind and then I was doing this until the day before going to print. So that was the reason.

SW: I expected and I think many people in the UK would expect that as it is you writing a book it will be absolutely full of contemporary music and nothing else. And it was really pleasant that it was so much more. It wasn’t just your personal history, it covers everything about the bass clarinet … was that your intention?

HS: Yes. That was my intention. That’s why I am really pleased and I am especially pleased with the critics and comments on the book because everybody is mentioning what you are saying and that was what I wanted. I have read a lot of serious books and that’s not me – I love jokes, I love life. I cannot write a complete serious book because when I was writing for example about quarter tones immediately I was thinking of the bad things! That’s why I said that I didn’t want to write a book about the bass clarinet – I wanted to do it a personal way. I think I succeeded quite well. Still when I look at it and read it I am still laughing.

SW: You have many musical examples in your book. How did you go about selecting them?

HS: I was talking for example about notation and then I thought wait a moment I have a memory that is incredible. You say slap tongue on high F sharp and I remember a piece. I was writing quarter tones and I thought that piece is a beautiful example or there is that piece where they are not working. So it was always about what I wrote and then the piece came. I did not choose because it was a friend .. no no no. Or sometimes I had a piece that was so badly written down- but I love the composer. One piece for bass clarinet and harp was handwritten – so I cleaned it myself. It is very important that the music is very good in a book so the paper is beautiful, the book is beautiful and also the examples have to be beautiful.

SW: I also thought it would be full of contemporary extracts, but you have chosen all types of music from orchestral, to lyrical…

HS: But when you listen in my car I have Jazz music. I love Jazz music. I play contemporary music because I like it very much to play, but believe me in my house we nearly never listen to contemporary music.

SW: Looking to the future. One aspect I really like about the book is that it is full of information about other players so it is not at all a book just about you. I like the way that contact details are included for many players around the world.

HS: That is important and really I mean it. When I started and became more known the only thing I always had in mind was that I was afraid that when I stopped there would not be another idiot who is going on with the instrument. I do not worry anymore. I said in my book that we really have so many who are playing bass clarinet. But that was not when I started.

SW: I always say to my audiences that to be a bass clarinetist you have to be crazy!

HS: Yes you have to be crazy, but you will see I did not mention everybody that would be impossible. But you can see how many players we have now. People who are really playing bass clarinet and not just just because they have to play in orchestra. They really go on and influence composers. The only really selfish thing in the book is the repertoire list. It is my repertoire. That is the only thing that is me alone. Already that is 14/15 pages. But the rest … I was so happy when your recording came and I included it immediately in the book because I thought this is interesting because I don’t have a recording of that piece as it is not my repertoire. Do I ignore them? No, that would be stupid. I have an ideal of what is good – but that may not be others ideals. I don’t play Schoeck (sonate), but that doesn’t mean it is a bad piece of course – my students play Schoeck. I don’t play in orchestra, but my students are using Michael Drapkin’s orchestral excerpts books.

SW: Do you have any nice memories of concerts in the UK

HS: What I loved was the series with the composer Barry Anderson. He was the director of the West Square Electronic Music Group. And also Stephen Montague was there. I played a beautiful piece by Barry Anderson for bass clarinet, string quartet and electronics. I loved it very much and we played about 20 concerts all over the UK with the Arts Council. I also played the SOLO by Stockhausen and Monodies by Jonty Harrison. I love to be in England to play and we did a lot of things like when Jonathan Harvey wrote his Trio (Riot for bass clarinet, flute and piano). But I must be honest – the last ten years I did not visit England

Harry Sparnaay – “ A Personal History”, is really a must for everyone who wants to know more about the bass clarinet. It is a huge wealth of information from the history of the instrument to information on general techniques, contemporary techniques, repertoire, players from around the world and products associated with the instrument. It is written from the heart with much affection and humour.

The book is published by Periferia Music www.periferiamusic.com It can also be purchased in the UK at Howarths Music Shop in London.

Herbert Noord – music critic / the Netherlands

In pop music, especially in English a biography or autobiography of a famous pop star or group, is an accepted phenomenon. In recent decades dozens of those books have appeared. Keith Richards, Patti Smith and Sammy Hagar were recently responsible for this kind of book. Also in jazz it is not unusual to write a book about the live and times of an interesting musician. I have books in my library from Mingus and Miles to Chet Baker and Ben Webster

Biographies or autobiographies of Dutch (jazz) musicians are very rare, the only one I own are those of Cees Schrama and Rein de Graaff! In front of me is now a special edition. Special in multiple meanings. It is an autobiography of a Dutch musician who wrote at the same time a biography about an unusual instrument: the bass clarinet. The book is originally written in Dutch, translated into English and then published by a Spanish publisher.

Books written by musicians are not that usual, they are rare birds. Harry Sparnaay is such a rare bird. In this fascinating book, he describes his development to become an internationally acclaimed musician, his discovery of the bass clarinet and his contribution to the recognition of this instrument, often regarded with suspicion by the established musical elite.

What makes this book a special book? Not just the fact that in the Netherlands almost no books are and were written by musicians and published, but also the fact that reading is fun even for those readers who don’t belong to the order of bass clarinet players .

Why a review of this book is in a magazine that is mainly involved in jazz, is due to the link which exists between the writer and jazz. Harry made music for years with celebrities in the Amsterdam Bohemia Jazz Quintet and brought it later to performances with Theo Taldick’s famous big band. Although Harry’s musical life started with an accordion on his belly, his first love was the tenor saxophone. To become a jazz saxophonist was his dream. Young Harry heard the music of all the saxophonists that he could get his hands on, from Stan Getz to Coltrane and Hawkins to Young, to make that dream a reality. When he took his first steps in the Dutch jazz scene, it was with a tenor saxophone tied round his neck. But not after his father had decreed that he also should gain a solid musical background by studying at the Amsterdam conservatory. At that time, late fifties, early sixties, the tenor saxophone was a highly suspect instrument at the conservatories. The overall thought was that those kind of instruments were essentially played in dark cellars. It was “not done”.

Harry was allowed to do an entrance exam and played on his sax “Well You Need It” composed by Monk. His choice raised the eyebrows of the examination committee. Fortunately a member of the committee recognized a true musician and on the condition that Harry switched to clarinet they admitted him to become a conservatory student.

He studied clarinet diligently when at one point the teacher came in with a bass clarinet and invited his students to try this instrument. Harry tried also and discovered at the same time that this should become ‘his’ instrument. He became hooked on this wonderful instrument. The bass clarinet originated sometime between 1730 and 1750. It was the great Adolphe Sax in 1835, who made some important modifications and who set the standard that led to the current instrument.

Repertoire

Harry describes in his book, his relentless struggle for adequate modern repertoire for the bass clarinet. There were almost no written pieces for bass clarinet, and if they were aware of the instrument they had to be forced to compose for this instrument. Because of this lack of written material Harry created a self-imposed task, namely to encourage composers to write for his instrument. He succeeded wonderfully well. Keep in mind that the first concert for bass clarinet dates from 1955! There are now hundreds of compositions written for this instrument and more appear on a weekly basis. Harry may be blamed for this success.

There is an ample amount of this material by Harry recorded on sound carriers. So he is also featured on the newly released recordings of the Theo Loevendie consort. In this last group he had made his move to the bass clarinet and played with the tenor Hans Dulfer.

On another CD Harry had recorded a tribute to Eric Dolphy a bass clarinettist highly admired by Harry. The beautifully illustrated book includes many examples of notations, fingering diagrams for directions and advice concerning ‘How to build a repertoire’ and a clear explanation of the techniques of “circular breathing” and “multiphonics”.

What makes the book attractive not only for bass-clarinet musicians but also for a general reader is the clear but curiosity provoking way this matter is made accessible.

And for those who thought it was all very serious there are a lot of pages with wonderful stories and anecdotes.

“At the first rehearsal the conductor greeted me with the smell of a Scotch whisky distillery around him that almost floored me. It seemed to me that he already swallowed half the annual production of this Scottish distillery. I hoped that he would skip his drinking before the concert, but that was a bit naive, to put it mildly.

Indeed my hope proved to be thoroughly idle the next day. The conductor had consumed the other half of the annual production. There was a strong Scottish influence on changes and tempo. A strict supervision from the conductors-stand was out of the question.

As a soloist you can still get away at such a disaster but how about an entire orchestra? It ended up in one big cluster”.

Harry Sparnaay -The bass clarinet / a personal history Published by

Periferiamusic

www.periferiamusic.com

ISBN 978-84-93884-50-5

Think of the last time you played, maybe with friends, in a concert situation or in your bedroom or a practice room; choose a pleasant memory. Were you sitting or standing? Were there other people with you, other musicians and/or an audience? What clothes were you wearing? See the colours of the cloth, textures and feel of the material on your skin. What was the air like? Were you outside or in? Was it light or dimmer? Is the picture still or moving? Become more aware of movement. Feel the instrument in your hand, the pressure keys under your fingers, how were you breathing as you played or sang. Were you hot, warm or comfortable at room temperature? What did you play and for how long? Were you playing fast or slow, loud or soft? How many sounds were there? What was your tone like? As your memory becomes richer in detail, in your inner ear what direction does the sound come from? Feel your connection with the instrument grow. Feel the music you played in your body, it’s rhythm, harmonies and melodies… and make them louder in your mind’s ear. Enjoy the weight of your feet on the ground. Where in your body did you feel the music, allow this feeling to grow? Become aware of the notes as you played, the higher ones and lower ones. As this memory becomes clearer and more detailed, are you in the mental picture (associated)? Or are you looking at yourself in the picture (disassociated)? Is your picture focused or unfocused? Find the zoom lens of your camera and zoom in. Then step into the picture, make it brighter and panoramic (see all around you)…Now double the feeling and the passion… and then again. Do this as often as you like until you are totally there and more…

Think of the last time you played, maybe with friends, in a concert situation or in your bedroom or a practice room; choose a pleasant memory. Were you sitting or standing? Were there other people with you, other musicians and/or an audience? What clothes were you wearing? See the colours of the cloth, textures and feel of the material on your skin. What was the air like? Were you outside or in? Was it light or dimmer? Is the picture still or moving? Become more aware of movement. Feel the instrument in your hand, the pressure keys under your fingers, how were you breathing as you played or sang. Were you hot, warm or comfortable at room temperature? What did you play and for how long? Were you playing fast or slow, loud or soft? How many sounds were there? What was your tone like? As your memory becomes richer in detail, in your inner ear what direction does the sound come from? Feel your connection with the instrument grow. Feel the music you played in your body, it’s rhythm, harmonies and melodies… and make them louder in your mind’s ear. Enjoy the weight of your feet on the ground. Where in your body did you feel the music, allow this feeling to grow? Become aware of the notes as you played, the higher ones and lower ones. As this memory becomes clearer and more detailed, are you in the mental picture (associated)? Or are you looking at yourself in the picture (disassociated)? Is your picture focused or unfocused? Find the zoom lens of your camera and zoom in. Then step into the picture, make it brighter and panoramic (see all around you)…Now double the feeling and the passion… and then again. Do this as often as you like until you are totally there and more…