Clarinet

The clarinet is a musical-instrument family belonging to the group known as the woodwind instruments. It has a single-reed mouthpiece, a straight cylindrical tube with an almost cylindrical bore, and a flared bell. A person who plays a clarinet is called a clarinetist (sometimes spelled clarinettist).

The word clarinet may have entered the English language via the French clarinette (the feminine diminutive of Old French clarin or clarion), or from Provençal clarin, “oboe”. It would seem however that its real roots are to be found amongst some of the various names for trumpets used around the renaissance and baroque eras. Clarion, clarin and the Italian clarino are all derived from the medieval term claro which referred to an early form of trumpet. This is probably the origin of the Italian clarinetto, itself a diminutive of clarino, and consequently of the European equivalents such as clarinette in French or the German Klarinette. According to Johann Gottfried Walther, writing in 1732, the reason for the name is that “it sounded from far off not unlike a trumpet”. The English form clarinet is found as early as 1733, and the now-archaic clarionet appears from 1784 until the early years of the 20th century.

While the similarity in sound between the earliest clarinets and the trumpet may hold a clue to its name, other factors may have been involved. During the late baroque era, composers such as Bach and Handel were making new demands on the skills of their trumpeters, who were often required to play difficult melodic passages in the high, or as it came to be called, clarion register. Since the trumpets of this time had no valves or pistons, melodic passages would often require the use of the highest part of the trumpet’s range, where the harmonics were close enough together to produce scales of adjacent notes as opposed to the gapped scales or arpeggios of the lower register. The trumpet parts that required this speciality were known by the term clarino and this in turn came to apply to the musicians themselves. It is probable that the term clarinet may stem from the diminutive version of the ‘clarion’ or ‘clarino’ and it has been suggested that clarino players may have helped themselves out by playing particularly difficult passages on these newly developed “mock trumpets”.

Johann Christoph Denner is generally believed to have invented the clarinet in Germany around the year 1700 by adding a register key to the earlier chalumeau. Over time, additional keywork and airtight pads were added to improve the tone and playability.

These days the most popular clarinet is the B♭ clarinet. However, the clarinet in A, just a semitone lower, is commonly used in orchestral music. Since the middle of the 19th century the bass clarinet (nowadays invariably in B♭ but with extra keys to extend the register down a few notes) has become an essential addition to the orchestra. The clarinet family ranges from the (extremely rare) BBB♭ octo-contrabass to the A♭ piccolo clarinet. The clarinet has proved to be an exceptionally flexible instrument, equally at home in the classical repertoire as in concert bands, military bands, marching bands, klezmer, and jazz.

The cylindrical bore is primarily responsible for the clarinet’s distinctive timbre, which varies between its three main registers, known as the chalumeau and clarion. The tone quality can vary greatly with the musician, the music, the instrument, the mouthpiece, and the reed. The differences in instruments and geographical isolation of players in different countries led to the development, from the last part of the 18th century onwards, of several different schools of clarinet playing. The most prominent were the German/Viennese traditions and the French school. The latter was centered on the clarinetists of the Conservatoire de Paris. The proliferation of recorded music has made examples of different styles of clarinet playing available. The modern clarinetist has a diverse palette of “acceptable” tone qualities to choose from.

Bass Clarinet

The A clarinet and B♭ clarinet have nearly the same bore, and use the same mouthpiece. Orchestral players using the A and B♭ instruments in the same concert could use the same mouthpiece (and often the same barrel) for both (see ‘usage’ below). The A and the B♭ instruments have nearly identical tonal quality, although the A typically has a slightly warmer sound. The tone of the E♭ clarinet is brighter than that of the lower clarinets and can be heard even through loud orchestral or concert band textures. The bass clarinet has a characteristically deep, mellow sound, while the alto clarinet is similar in tone to the bass (though not as dark).

Range

Main articles: clarinet family, E-flat clarinet, soprano clarinet, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, basset-horn, contra-alto clarinet and contrabass clarinet

Clarinets have the largest pitch range of common woodwinds. The intricate key organization that makes this range possible can make the playability of some passages awkward. The bottom of the clarinet’s written range is defined by the keywork on each instrument, standard keywork schemes allowing a low E on the common B♭ clarinet. The lowest concert pitch depends on the transposition of the instrument in question. The nominal highest note of the B♭ clarinet is a semitone higher than the highest note of the oboe. Since the clarinet has a wider range of notes, the lowest note of the B♭ clarinet is significantly deeper (a minor or major sixth) than the lowest note of the oboe.

Nearly all soprano and piccolo clarinets have keywork enabling them to play the E below middle C as their lowest written note (in scientific pitch notation that sounds D3 on a soprano clarinet or C4, i.e. concert middle C, on a piccolo clarinet), though some B♭ clarinets go down to E♭3 to enable them to match the range of the A clarinet. On the B♭ soprano clarinet, the concert pitch of the lowest note is D3, a whole tone lower than the written pitch. Most alto and bass clarinets have an extra key to allow a (written) E♭3. Modern professional-quality bass clarinets generally have additional keywork to written C3. Among the less commonly encountered members of the clarinet family, contra-alto and contrabass clarinets may have keywork to written E♭3, D3, or C3; the basset clarinet and basset horn generally go to low C3.

Defining the top end of a clarinet’s range is difficult, since many advanced players can produce notes well above the highest notes commonly found in method books. G6 is usually the highest note clarinetists encounter in classical repertoire. The C above that (C7 i.e. resting on the fifth ledger line above the treble staff) is attainable by advanced players and is shown on many fingering charts, and fingerings as high as G7 exist.

The range of a clarinet can be divided into three distinct registers. The lowest register, from low written E to the written B♭ above middle C (B♭4), is known as the chalumeau register (named after the instrument that was the clarinet’s immediate predecessor). The middle register is known as the clarion register (sometimes in the U.S.A. as the clarino register from the Italian) and spans just over an octave (from written B above middle C (B4) to the C two octaves above middle C (C6)); it is the dominant range for most members of the clarinet family. The top or altissimo register consists of the notes above the written C two octaves above middle C (C6). All three registers have characteristically different sounds. The chalumeau register is rich and dark. The clarion register is brighter and sweet, like a trumpet (clarion) heard from afar. The altissimo register can be piercing and sometimes shrill.

Acoustics

Sound wave propagation in the soprano clarinet

Sound is a wave that propagates through the air as a result of a local variation in air pressure. The production of sound by a clarinet follows these steps:

The mouthpiece and reed are surrounded by the player’s lips, which put light, even pressure on the reed and form an airtight seal. Air is blown past the reed and down the instrument. In the same way that a flag flaps in the breeze, the air rushing past the reed causes it to vibrate. As air pressure from the mouth increases, the amount the reed vibrates increases until the reed hits the mouthpiece. At this point the reed stays pressed against the mouthpiece until either the springiness of the reed forces it to open, or a returning pressure wave ‘bumps’ into the reed and opens it. Each time the reed opens, a puff of air goes through the gap, after which the reed swings shut again. When played loudly, the reed can spend up to 50% of the time shut. The ‘puff of air’ or compression wave (around 3% greater pressure than the surrounding air) travels down the cylindrical tube and escapes at the point where the tube opens out. This is either at the closest open hole or at the end of the tube.

.

More than a ‘neutral’ amount of air escapes from the instrument, which creates a slight vacuum or rarefaction in the clarinet tube. This rarefaction wave travels back up the tube.

The rarefaction is reflected off the sloping end wall of the clarinet mouthpiece. The opening between the reed and the mouthpiece makes very little difference to the reflection of the rarefaction wave. This is because the opening is very small compared to the size of the tube, so almost the entire wave is reflected back down the tube even if the reed is completely open at the time the wave hits.

When the rarefication wave reaches the other (open) end of the tube, air rushes in to fill the slight vacuum. A little more than a ‘neutral’ amount of air enters the tube and causes a compression wave to travel back up the tube. Once the compression wave reaches the mouthpiece end of the clarinet ‘tube’, it is reflected again back down the pipe. However at this time, either because the compression wave ‘bumped’ the reed or because of the natural vibration cycle of the reed, the gap opens and another ‘puff’ of air is sent down the pipe.

The original compression wave, now greatly reinforced by the second ‘puff’ of air, sets off on another two trips down the pipe (travelling 4 pipe lengths in total) before the cycle is repeated again.

The cycle repeats at a frequency relative to how long it takes a wave to travel to the first open hole and back twice (i.e. four times the length of the pipe). For example: when all the holes bar the very top one are open (i.e. the trill ‘B’ key is pressed), the note A4 (440 Hz) is produced. This represents a repeat of the cycle 440 times per second.

In addition to this primary compression wave, other waves, known as harmonics, are created. Harmonics are caused by factors including: the imperfect wobbling and shaking of the clarinet reed, the reed sealing the mouthpiece opening for part of the wave cycle (which creates a flattened section of the sound wave) and imperfections (bumps and holes) in the clarinet bore. A wide variety of compression waves are created, but only some (primarily the odd harmonics) are reinforced. These extra waves are what gives the clarinet its characteristic tone.

The bore of the clarinet is cylindrical for most of the tube with an inner bore diameter between 14 and 15.5 millimetres (0.55 and 0.61 in), but there is a subtle hourglass shape, with the thinnest part below the junction between the upper and lower joint. The reduction is 1 to 3 millimetres (0.039 to 0.118 in) depending on the maker. This “hourglass” shape, although not visible to the naked eye, helps to correct the pitch/scale discrepancy between the chalumeau and clarion registers (perfect 12th). The diameter of the bore affects characteristics such as available harmonics, timbre, and pitch stability (how far the player can bend a note in the manner required in jazz and other music). The bell at the bottom of the instrument flares out to improve the tone and tuning of the lowest notes.

Most modern clarinets have “undercut” tone holes that improve intonation and sound. Undercutting means chamfering the bottom edge of tone holes inside the bore. Acoustically, this makes the tone hole function as if it were larger, but its main function is to allow the air column to follow the curve up through the tone hole (surface tension) instead of “blowing past” it under the increasingly directional frequencies of the upper registers.

The fixed reed and fairly uniform diameter of the clarinet give the instrument an acoustical behavior approximating that of a cylindrical stopped pipe. Recorders use a tapered internal bore to overblow at the 8th (octave) when its thumb/register hole is pinched open while the clarinet, with its cylindrical bore, overblows on the 12th. Adjusting the angle of the bore taper controls the frequencies of the overblown notes (harmonics). Changing the mouthpiece’s tip opening and the length of the reed changes aspects of the harmonic timbre or voice of the instrument because this changes the speed of reed vibrations. Generally, the goal of the clarinetist when producing a sound is to make as much of the reed vibrate as possible, making the sound fuller, warmer, and potentially louder.

The lip position and pressure, the shaping of the vocal tract, the choice of reed and mouthpiece, the amount of air pressure created, and the evenness of the air flow account for most of the player’s ability to control the tone of a clarinet. A highly skilled musician will provide the ideal lip pressure and air pressure for each frequency (note) being produced. They will have an embouchure which places an even pressure across the reed by carefully controlling their lip muscles. The air flow will also be carefully controlled by using the strong stomach muscles (as opposed to the weaker and erratic chest muscles) and they will use the diaphragm to oppose the stomach muscles to achieve a tone softer than a forte, rather than weakening the stomach muscle tension to lower air pressure. Their vocal tract will be shaped to resonate at frequencies associated with the tone being produced.

Covering or uncovering the tone holes varies the length of the pipe, changing the resonant frequencies of the enclosed air column and hence the pitch of the sound. A clarinetist moves between the chalumeau and clarion registers through use of the register key, or speaker key: clarinetists call the change from chalumeau register to clarion register “the break”. The open register key stops the fundamental frequency from being reinforced and the reed is forced to vibrate at three times the speed it was originally vibrating at. This produces a note a twelfth above the original note. Most instruments overblow at two times the speed of the fundamental frequency (the octave) but as the clarinet acts as a closed pipe system, the reed cannot vibrate at twice the original speed because it would be creating a ‘puff’ of air at the time the previous ‘puff’ is returning as a rarefaction. This means that it cannot be reinforced and so would die away.

The chalumeau register plays fundamentals, whereas the clarion register, aided by the register key, plays third harmonics, a perfect twelfth higher than the fundamentals. The first several notes of the altissimo range, aided by the register key and venting with the first left-hand hole, play fifth harmonics, a major seventeenth (that is a perfect twelfth plus a major sixth) above the fundamental. The clarinet is therefore said to overblow at the twelfth, and when moving to the altissimo register, a seventeenth. By contrast, nearly all other woodwind instruments overblow at the octave, or like the ocarina and tonette, do not overblow at all). A clarinet must have holes and keys for nineteen notes (a chromatic octave and a half, from bottom E to B♭) in its lowest register to play the chromatic scale. This overblowing behavior explains the clarinet’s great range and complex fingering system. The fifth and seventh harmonics are also available, sounding a further sixth and fourth (a flat, diminished fifth) higher respectively; these are the notes of the altissimo register. This is also why the inner “waist” measurement is so critical to these harmonic frequencies.

The highest notes on a clarinet can have a shrill piercing quality and can be difficult to tune accurately. Different instruments often play differently in this respect due to the sensitivity of the bore and reed measurements. Using alternate fingerings and adjusting the embouchure help correct the pitch of these higher notes.

Since approximately 1850, clarinets have been nominally tuned according to twelve-tone equal temperament. Older clarinets were nominally tuned to mean-tone. A skilled performer can use his or her embouchure to considerably alter the tuning of individual notes or to produce vibrato, a pulsating change of pitch often employed in jazz. Vibrato is rare in classical or concert band literature; however, certain clarinetists, such as Richard Stoltzman, do use vibrato in classical music. Special fingerings may be used to play quarter tones and other micro-tonal intervals. Around 1900, Dr. Richard H. Stein, a Berlin musicologist, made a quarter-tone clarinet, which was soon abandoned. Years later, another German, Fritz Schüller of Markneukirchen, built a quarter tone clarinet, with two parallel bores of slightly different lengths whose tone holes are operated using the same keywork and a valve to switch from one bore to the other.

The construction of a clarinet (Oehler system)

Materials

Clarinet bodies have been made from a variety of materials including wood, plastic, hard rubber, metal, resin, and ivory. The vast majority of clarinets used by professional musicians are made from African hardwood, mpingo (African Blackwood) or grenadilla, rarely (because of diminishing supplies) Honduran rosewood and sometimes even cocobolo. Historically other woods, notably boxwood, were used.

Most modern, inexpensive instruments are made of plastic resin, such as ABS. These materials are sometimes called resonite, which is Selmer’s trademark name for its type of plastic. Metal soprano clarinets were popular in the early 20th century, until plastic instruments supplanted them; metal construction is still used for the bodies of some contra-alto and contrabass clarinets, and for the necks and bells of nearly all alto and larger clarinets. Ivory was used for a few 18th-century clarinets, but it tends to crack and does not keep its shape well.

Mouthpieces are generally made of hard rubber, although some inexpensive mouthpieces may be made of plastic. Other materials such as crystal/glass, wood, ivory, and metal have also been used. Ligatures are often made out of metal and plated in nickel, silver, or gold. Other ligature materials include wire, wire mesh, plastic, naugahyde, string, or leather.

The Reed

The instrument uses a single reed made from the cane of Arundo donax, a type of grass. Reeds may also be manufactured from synthetic materials. The ligature fastens the reed to the mouthpiece. When air is blown through the opening between the reed and the mouthpiece facing, the reed vibrates and produces the instrument’s sound.

Basic reed measurements are as follows: tip, 12 millimetres (0.47 in) wide; lay, 15 millimetres (0.59 in) long (distance from the place where the reed touches the mouthpiece to the tip); gap, 1 millimetre (0.039 in) (distance between the underside of the reed tip and the mouthpiece). Adjustment to these measurements is one method of affecting tone color.

Most clarinetists buy manufactured reeds, although many make adjustments to these reeds and some make their own reeds from cane “blanks”. Reeds come in varying degrees of hardness, generally indicated on a scale from one (soft) through five (hard). This numbering system is not standardized—reeds with the same hardness number often vary in hardness across manufacturers and models. Reed and mouthpiece characteristics work together to determine ease of playability, pitch stability, and tonal characteristics.

Components

Note: A Boehm system soprano clarinet is shown in the photos illustrating this section. However, all modern clarinets have similar components.

Clarinet reed, mouthpiece, and ligature

The reed is attached to the mouthpiece by the ligature, and the top half-inch or so of this assembly is held in the player’s mouth. In the past clarinetists used to wrap a string around the mouthpiece and reed instead of using a ligature. The formation of the mouth around the mouthpiece and reed is called the embouchure.

Bb Clarinet reed and mouthpiece.

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The reed is on the underside of the mouthpiece, pressing against the player’s lower lip, while the top teeth normally contact the top of the mouthpiece (some players roll the upper lip under the top teeth to form what is called a ‘double-lip’ embouchure). Adjustments in the strength and shape of the embouchure change the tone and intonation (tuning). It is not uncommon for clarinetists to employ methods to relieve the pressure on the upper teeth and inner lower lip by attaching pads to the top of the mouthpiece or putting (temporary) padding on the front lower teeth, commonly from folded paper.

Barrel of a B♭ soprano clarinet

Next is the short barrel; this part of the instrument may be extended to fine-tune the clarinet. As the pitch of the clarinet is fairly temperature-sensitive, some instruments have interchangeable barrels whose lengths vary slightly. Additional compensation for pitch variation and tuning can be made by pulling out the barrel and thus increasing the instrument’s length, particularly common in group playing in which clarinets are tuned to other instruments (such as in an orchestra or concert band). Some performers use a plastic barrel with a thumb-wheel that adjusts the barrel length. On basset horns and lower clarinets, the barrel is normally replaced by a curved metal neck.

Upper joint of a Boehm system clarinet

The main body of most clarinets is divided into the upper joint, the holes and most keys of which are operated by the left hand, and the lower joint with holes and most keys operated by the right hand. Some clarinets have a single joint: on some basset horns and larger clarinets the two joints are held together with a screw clamp and are usually not disassembled for storage. The left thumb operates both a tone hole and the register key. On some models of clarinet, such as many Albert system clarinets and increasingly some higher-end Boehm system clarinets, the register key is a ‘wraparound’ key, with the key on the back of the clarinet and the pad on the front. Advocates of the wraparound register key say it improves sound, and it is harder for moisture to accumulate in the tube beneath the pad. Nevertheless, there is a consensus among repair techs that this type of register key is harder to keep in adjustment, i.e., it is hard to have enough spring pressure to close the hole securely.

The body of a modern soprano clarinet is equipped with numerous tone holes of which seven (six front, one back) are covered with the fingertips, and the rest are opened or closed using a set of keys. These tone holes let the player produce every note of the chromatic scale. On alto and larger clarinets, and a few soprano clarinets, key-covered holes replace some or all finger holes. The most common system of keys was named the Boehm system by its designer Hyacinthe Klosé in honour of flute designer Theobald Boehm, but it is not the same as the Boehm system used on flutes. The other main system of keys is called the Oehler system and is used mostly in Germany and Austria (see History). The related Albert system is used by some jazz, klezmer, and eastern European folk musicians. The Albert and Oehler systems are both based on the early Mueller system.

Lower Joint of a Boehm system clarinet

The cluster of keys at the bottom of the upper joint (protruding slightly beyond the cork of the joint) are known as the trill keys and are operated by the right hand. These give the player alternative fingerings that make it easy to play ornaments and trills. The entire weight of the smaller clarinets is supported by the right thumb behind the lower joint on what is called the thumb-rest. Basset horns and larger clarinets are supported with a neck strap or a floor peg.

Bell of a B♭ soprano clarinet

Finally, the flared end is known as the bell. Contrary to popular belief, the bell does not amplify the sound; rather, it improves the uniformity of the instrument’s tone for the lowest notes in each register. For the other notes the sound is produced almost entirely at the tone holes and the bell is irrelevant. On basset horns and larger clarinets, the bell curves up and forward and is usually made of metal.

Keywork

Theobald Boehm did not directly invent the key system of the clarinet. Boehm was a flautist who created the key system that is now used for the transverse flute. Klosé and Buffet applied Boehm’s system to the clarinet. Although the credit goes to those people, Boehm’s name was given to that key system because it was based on that used for flute.

The current Boehm key system consists of generally 6 rings, on the thumb, 1st, 2nd, 4th, 5th and 6th holes, a register key just above the thumb hole, easily accessible with the thumb. Above the 1st hole, there is a key that lifts two covers creating the note A in the throat register (high part of low register) of the clarinet. A key at the side of the instrument at the same height as the A key lifts only one of the two covers, producing G♯ a semitone lower. The A key can be used in conjunction solely with the register key to produce A♯/B♭.

History

4-key boxwood clarinet, ca. 1760.

Lineage

The clarinet has its roots in the early single-reed instruments or hornpipes used in Ancient Greece, old Egypt, Middle East, and Europe since the Middle Ages, such as the albogue, alboka, and double clarinet.

The modern clarinet developed from a Baroque instrument called the chalumeau. This instrument was similar to a recorder, but with a single-reed mouthpiece and a cylindrical bore. Lacking a register key, it was played mainly in its fundamental register, with a limited range of about one and a half octaves. It had eight finger holes, like a recorder, and two keys for its two highest notes. At this time, contrary to modern practice, the reed was placed in contact with the upper lip.

Around the turn of the 18th century, the chalumeau was modified by converting one of its keys into a register key to produce the first clarinet. This development is usually attributed to German instrument maker Johann Christoph Denner, though some have suggested his son Jacob Denner was the inventor. This instrument played well in the middle register with a loud, shrill sound, so it was given the name clarinetto meaning “little trumpet” (from clarino + -etto). Early clarinets did not play well in the lower register, so players continued to play the chalumeaux for low notes. As clarinets improved, the chalumeau fell into disuse, and these notes became known as the chalumeau register. Original Denner clarinets had two keys, and could play a chromatic scale, but various makers added more keys to get improved tuning, easier fingerings, and a slightly larger range. The classical clarinet of Mozart’s day typically had eight finger holes and five keys.

Clarinets were soon accepted into orchestras. Later models had a mellower tone than the originals. Mozart (d. 1791) liked the sound of the clarinet (he considered its tone the closest in quality to the human voice) and wrote numerous pieces for the instrument. By the time of Beethoven (c. 1800–1820), the clarinet was a standard fixture in the orchestra.

Pads

The next major development in the history of clarinet was the invention of the modern pad. Because early clarinets used felt pads to cover the tone holes, they leaked air. This required pad-covered holes to be kept to a minimum, restricting the number of notes the clarinet could play with good tone. In 1812, Iwan Müller, a Baltic German community-born clarinetist and inventor, developed a new type of pad that was covered in leather or fish bladder. It was airtight and let makers increase the number of pad-covered holes. Müller designed a new type of clarinet with seven finger holes and thirteen keys. This allowed the instrument to play in any key with near-equal ease. Over the course of the 19th-century makers made many enhancements to Mueller’s clarinet, such as the Albert system and the Baermann system, all keeping the same basic design. Modern instruments may also have cork or synthetic pads.

Oehler system clarinets use additional tone holes to correct intonation (patent C♯, low E-F correction, fork-F/B♭ correction and fork B♭ correction)

The final development in the modern design of the clarinet used in most of the world today was introduced by Hyacinthe Klosé in 1839. He devised a different arrangement of keys and finger holes, which allow simpler fingering. It was inspired by the Boehm system developed for flutes by Theobald Boehm. Klosé was so impressed by Boehm’s invention that he named his own system for clarinets the Boehm system, although it is different from the one used on flutes. This new system was slow to gain popularity but gradually became the standard, and today the Boehm system is used everywhere in the world except Germany and Austria. These countries still use a direct descendant of the Mueller clarinet known as the Oehler system clarinet. Also, some contemporary Dixieland players continue to use Albert system clarinets.

Use of multiple clarinets

The modern orchestral standard of using soprano clarinets in both B♭ and A has to do partly with the history of the instrument, and partly with acoustics, aesthetics, and economics. Before about 1800, due to the lack of airtight pads (see History), practical woodwinds could have only a few keys to control accidentals (notes outside their diatonic home scales). The low (chalumeau) register of the clarinet spans a twelfth (an octave plus a perfect fifth), so the clarinet needs keys/holes to produce all nineteen notes in that range. This involves more keywork than is necessary on instruments that “overblow” at the octave—oboes, flutes, bassoons, and saxophones, for example, which need only twelve notes before overblowing.

Clarinets with few keys cannot therefore easily play chromatically, limiting any such instrument to a few closely related key signatures. For example, an eighteenth-century clarinet in C could be played in F, C, and G (and their relative minors) with good intonation, but with progressive difficulty and poorer intonation as the key moved away from this range. In contrast, for octave-overblowing instruments, an instrument in C with few keys could much more readily be played in any key.

This problem was overcome by using three clarinets—in A, B♭, and C—so that early 19th-century music, which rarely strayed into the remote keys (five or six sharps or flats), could be played as follows: music in 5 to 2 sharps (B major to D major concert pitch) on A clarinet (D major to F major for the player), music in 1 sharp to 1 flat (G to F) on C clarinet, and music in 2 flats to 4 flats (B♭ to A♭) on the B♭ clarinet (C to B♭ for the player). Difficult key signatures and numerous accidentals were thus largely avoided.

With the invention of the airtight pad, and as key technology improved and more keys were added to woodwinds, the need for clarinets in multiple musical keys was reduced. However, the use of multiple instruments in different keys persisted, with the three instruments in C, B♭, and A all used as specified by the composer.

The lower-pitched clarinets sound more “mellow” (less bright), and the C clarinet—being the highest and therefore brightest of the three—fell out of favour as the other two clarinets could cover its range and their sound was considered better. While the clarinet in C began to fall out of general use around 1850, some composers continued to write C parts after this date, e.g., Bizet’s Symphony in C (1855), Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 2 (1872), Smetana’s overture to The Bartered Bride (1866) and Má Vlast (1874), Dvořák’s Slavonic Dance Op. 46, No. 1 (1878), Brahms’ Symphony No. 4 (1885), Mahler’s Symphony No. 6 (1906), and Richard Strauss deliberately reintroduced it[clarification needed] to take advantage of its brighter tone, as in Der Rosenkavalier (1911).

While technical improvements and an equal-tempered scale reduced the need for two clarinets, the technical difficulty of playing in remote keys persisted, and the A has thus remained a standard orchestral instrument. In addition, by the late 19th century, the orchestral clarinet repertoire contained so much music for clarinet in A that the disuse of this instrument was not practical. Attempts were made to standardise to the B♭ instrument between 1930 and 1950 (e.g., tutors recommended learning the routine transposition of orchestral A parts on the B♭ clarinet, including solos written for A clarinet, and some manufacturers provided a low E♭ on the B♭ to match the range of the A), but this failed in the orchestral sphere.

Similarly there have been E♭ and D instruments in the upper soprano range, B♭, A, and C instruments in the bass range, and so forth; but over time the E♭ and B♭ instruments have become predominant.

The B♭ instrument remains dominant in concert bands and in jazz. Both B♭ and C instruments are used in some ethnic traditions, such as klezmer music.

Classical Music

A pair of Boehm system soprano clarinets—one in B♭ and one in A.

In classical music, clarinets are part of standard orchestral and concert band instrumentation.

The orchestra frequently includes two clarinetists playing individual parts—each player is usually equipped with a pair of standard clarinets in B♭ and A, and clarinet parts commonly alternate between B♭ and A instruments several times over the course of a piece or even, less commonly, of a movement (e.g., 1st movement Brahms 3rd symphony). Clarinet sections grew larger during the last few decades of the 19th century, often employing a third clarinetist, an E♭ or a bass clarinet. In the 20th century, composers such as Igor Stravinsky, Richard Strauss, Gustav Mahler, and Olivier Messiaen enlarged the clarinet section on occasion to up to nine players, employing many different clarinets including the E♭ or D soprano clarinets, basset horn, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, and/or contrabass.

In concert bands, clarinets are an important part of the instrumentation. The E♭ clarinet, B♭ clarinet, alto clarinet, bass clarinet, and contra-alto/contrabass clarinet are commonly used in concert bands. Concert bands generally have multiple B♭ clarinets; there are commonly 3 B♭ clarinet parts with 2–3 players per part. There is generally only one player per part on the other clarinets. There are not always E♭ clarinet, alto clarinet, and contra-alto clarinets/contrabass clarinet parts in concert band music, but all three are quite common.

This practice of using a variety of clarinets to achieve coloristic variety was common in 20th-century classical music and continues today. However, many clarinetists and conductors prefer to play parts originally written for obscure instruments on B♭ or E♭ clarinets, which are often of better quality and more prevalent and accessible.

The clarinet is widely used as a solo instrument. The relatively late evolution of the clarinet (when compared to other orchestral woodwinds) has left solo repertoire from the Classical period and later, but few works from the Baroque era. Many clarinet concertos have been written to showcase the instrument, with the concerti by Mozart, Copland, and Weber being well known.

Many works of chamber music have also been written for the clarinet. Common combinations are:

Clarinet and piano (including sonatas)

Clarinet trio; clarinet, piano, and another instrument (for example, string instrument or voice)

Clarinet quartet: various combinations including four B♭ clarinets, three B♭ clarinets and bass clarinet, two B♭ clarinets, alto clarinet and bass, and other possibilities such as the use of a basset horn, especially in European classical works.

Clarinet quintet, generally made up of a clarinet plus a string quartet.

Reed quintet, consists of oboe (doubling English horn), clarinet, alto saxophone (doubling soprano saxophone), bass clarinet, and bassoon.

Wind quintet, consists of flute, oboe, clarinet, bassoon, and horn.

Trio d’anches, or trio of reeds consists of oboe, clarinet, and bassoon.

Wind octet, consists of pairs of oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns.

Jazz

The clarinet was originally a central instrument in jazz, beginning with the New Orleans players in the 1910s. It remained a signature instrument of jazz music through much of the big band era into the 1940s. American players Jimmy Hamilton, Sidney Bechet, Alphonse Picou, Larry Shields, Jimmie Noone, Johnny Dodds, were all pioneers of the instrument in jazz. The B♭ soprano was the most common instrument, but a few early jazz musicians such as Louis Nelson Delisle and Alcide Nunez preferred the C soprano, and many New Orleans jazz brass bands have used E♭ soprano.

Swing clarinetists such as Benny Goodman, Artie Shaw, and Woody Herman led successful big bands and smaller groups from the 1930s onward. Duke Ellington, active from the 1920s to the 1970s, used the clarinet as lead instrument in his works, with several players of the instrument (Barney Bigard, Jimmy Hamilton, and Russell Procope) spending a significant portion of their careers in his orchestra. Harry Carney, primarily Ellington’s baritone saxophonist, occasionally doubled on bass clarinet. Meanwhile, Pee Wee Russell had a long and successful career in small groups.

With the decline of the big bands’ popularity in the late 1940s, the clarinet faded from its prominent position in jazz. By that time, an interest in Dixieland or traditional New Orleans jazz had revived; Pete Fountain was one of the best known performers in this genre. Bob Wilber, active since the 1950s, is a more eclectic jazz clarinetist, playing in several classic jazz styles. During the 1950s and 1960s, Britain underwent a surge in the popularity of what was termed ‘Trad jazz’. In 1956 the British clarinetist Acker Bilk founded his own ensemble. Several singles recorded by Bilk reached the British pop charts, including the ballad “Stranger on the Shore”.

The clarinet’s place in the jazz ensemble was usurped by the saxophone, which projects a more powerful sound and uses a less complicated fingering system. The requirement for an increased speed of execution in modern jazz also did not favour the clarinet, but the clarinet did not entirely disappear. A few players such as Buddy DeFranco, Tony Scott, and Jimmy Giuffre emerged during the 1950s playing bebop or other styles. A little later, Eric Dolphy (on bass clarinet), Perry Robinson, John Carter, Theo Jörgensmann, and others used the clarinet in free jazz. The French composer and clarinetist Jean-Christian Michel initiated a jazz-classical cross-over on the clarinet with the drummer Kenny Clarke.

In the U.S., the prominent players on the instrument since the 1980s have included Eddie Daniels, Don Byron, Marty Ehrlich, and others playing the clarinet in more contemporary contexts.

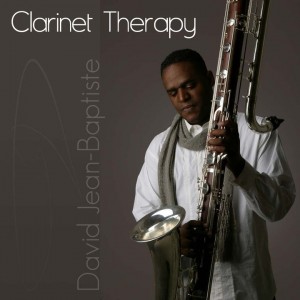

The clarinet is uncommon, but not unheard of in rock music. Jerry Martini played clarinet on Sly and the Family Stone’s 1968 hit, “Dance to the Music”; Don Byron, a founder of the Black Rock Coalition who was a member of hard rock guitarist Vernon Reid’s band, plays clarinet on the Mistaken Identity album (1996). The Beatles, Pink Floyd, Radiohead, Aerosmith, Billy Joel, and Tom Waits have also all used clarinet on occasion. Modern day clarinetist include the likes of Matthias Muller, David Jean-Baptiste and Felix Peikli to name a few.

Clarinets feature prominently in klezmer music, which entails a distinctive style of playing. The use of quarter-tones requires a different embouchure. Some klezmer musicians prefer Albert system clarinets.

The popular Brazilian music styles of choro and samba use the clarinet. Prominent contemporary players include Paulo Moura, Naylor ‘Proveta’ Azevedo, Paulo Sérgio dos Santos and Paquito D’Rivera.

Even though it has been adopted recently in Albanian folklore (around the 18th century), the clarinet, or gërneta as it is called, is one of the most important instruments in Albania, especially in the central and southern areas. The clarinet plays a crucial role in saze (folk ensemble) that perform in weddings and other celebrations. It is worth mentioned that the kaba (instrumental Albanian Isopolyphony included in UNESCO’s intangible cultural heritage list) is a very characteristic play of these ensembles. There are many clarinet players in Albania; arguably the most famous are Selim Leskoviku, Gaqo Lena, Remzi Lela (Çobani), Laver Bariu (Ustai), and Nevruz Nure (Lulushi i Korçës).

The clarinet is prominent in Bulgarian wedding music, an offshoot of Roma/Romani traditional music. Ivo Papazov is a well-known clarinetist in this genre. In Moravian dulcimer bands, the clarinet is usually the only wind instrument among string instruments.

In the Republic of Macedonia, old-town folk music -called chalgija (“чалгија”), the clarinet has the most important role in wedding music; clarinet solos mark the high point of dancing euphoria. One of the most renowned Macedonian clarinet players is Tale Ognenovski, who gained worldwide fame for his virtuosity.

In Greece the clarinet (usually referred to as “κλαρίνο”—”clarino”) is prominent in traditional music, especially in central, northwest and northern Greece (Thessaly, Epirus and Macedonia). The double-reed zurna was the dominant woodwind instrument before the clarinet arrived in the country, although many Greeks regard the clarinet as a native instrument. Traditional dance music, wedding music and laments include a clarinet soloist and quite often improvisations. Petroloukas Chalkias is a famous clarinetist in this genre.

The instrument is equally famous in Turkey, especially the lower pitched clarinet in G. The western European clarinet crossed via Turkey to Arabic music, where it is widely used in Arabic pop, especially if the intention of the arranger is to imitate the Turkish style.

Turkish clarinet

Also in Turkish folk music, a clarinet-like woodwind instrument, the sipsi, is used. However, it’s far more rare than the soprano clarinet and is mainly limited to folk music of the Aegean Region.

Groups of clarinets

Contrabass and contra-alto clarinets

Groups of clarinets playing together have become increasingly popular among clarinet enthusiasts in recent years. Common forms are:

Clarinet choir, which features a large number of clarinets playing together, usually involves a range of different members of the clarinet family (see Extended family of clarinets). The homogeneity of tone across the different members of the clarinet family produces an effect with some similarities to a human choir.

Clarinet quartet, usually three B♭ sopranos and one B♭ bass, or two B♭, an E♭ alto clarinet, and a B♭ bass clarinet, or sometimes four B♭ sopranos.

Clarinet choirs and quartets often play arrangements of both classical and popular music, in addition to a body of literature specially written for a combination of clarinets by composers such as Arnold Cooke, Alfred Uhl, Lucien Caillet and Václav Nelhýbel.

Extended Family of Clarinets

There is a family of many differently pitched clarinet types, some of which are very rare. The following are the most important sizes, from highest to lowest:

Piccolo clarinet A♭ Now rare, used for Italian military music and some contemporary pieces for its sonority;

E-flat clarinet (soprano clarinet) E♭ It has a characteristically shrill timbre, and is used to great effect in the classical orchestra whenever a brighter, or sometimes a more rustic or comical sound is called for. Richard Strauss featured it as a solo instrument in his symphonic poem, Till Eulenspiegel. It is much used in the concert band repertoire where it helps out the piccolo flute in the higher register and is very compatible with other band instruments, especially those in B♭ and E♭.

Soprano clarinet in D This was, to the high pitched E♭ instrument, what the A clarinet is to the B♭. Advances in playing technique and the instrument’s mechanism meant that players could play parts for the D instrument on their E♭ thus making this instrument more and more expendable. Though a few early pieces were written for it, its repertoire is now very limited in Western music. Nonetheless Stravinsky included both the D and E♭ clarinets in his instrumentation for The Rite Of Spring.

Soprano clarinet in C

Although this clarinet was very common in the instrument’s earliest period, its use began to dwindle and by the second decade of the twentieth century it had become practically obsolete and disappeared from the orchestra. From the time of Mozart, many composers began to favour the mellower, lower pitched instruments and the timbre of the ‘C’ instrument may have been considered too bright. Also, to avoid having to carry an extra instrument which required another reed and mouthpiece, orchestral players preferred to play parts for this instrument on their Bb clarinets, transposing up a tone. It is enjoying a resurgence in popular musical styles such as Klezmer; as an instrument in schools, and in more historically accurate interpretations of the classical and Romantic repertoire such as the First and Fifth Symphonies of Beethoven.

B♭ clarinet The most common type: used in most styles of music. Usually the term clarinet on its own refers to this instrument. It was commonly used in early jazz and swing. This was the instrument of renowned and popular figures such as Sidney Bechet, Benny Goodman, Woody Herman and Artie Shaw.

Basset clarinet A is a Clarinet in A extended to a low C; used primarily to play Classical-era music. Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was written for this instrument, though it is frequently played in a version for the ordinary A clarinet. Basset clarinets in B♭ also exist; this instrument is required to play the obbligato to the aria “Parto, parto” in Mozart’s La Clemenza di Tito.

Basset-horn in F Similar in appearance to the alto, but differs in that it is pitched in F, has an extended range to low C, and has a narrower bore on most models. Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto was originally sketched out as a concerto for basset horn in G. Rarely used today.

Alto clarinet E♭ Sometimes referred to as the tenor clarinet. Its greater size and consequently lower pitch give it a rich, dark sonority but it lacks the projection of the larger bass clarinet. It is used in chamber music and concert bands, rarely in orchestras.

Bass clarinet in B♭ Invented in the 1770s it only became popular around a hundred years later when it contributed to the rich orchestral palettes of composers such as Wagner and the late Romantics. It has become a mainstay of the modern orchestra. Originally the third clarinet would double on bass but now most orchestras employ a specialist devoted principally to this instrument.

It is used in concert bands, contemporary music, and enjoys, along with the B♭ clarinet, a considerable rôle in jazz. Eric Dolphy was one of its more remarkable exponents.

Contra-alto clarinet (also called E♭ contrabass clarinet) EE♭ Used in clarinet choirs and is common in concert bands.

Contrabass clarinet (also called B♭ subcontrabass or double-bass clarinet) BB♭ Used in clarinet choirs and is common in concert bands. It is sometimes used in orchestras. Arnold Schoenberg calls for one in his Five Pieces for Orchestra.

Experimental EEE♭ and BBB♭ octocontra-alto and octocontrabass clarinets have also been built. There have also been soprano clarinets in C, A, and B♭ with curved barrels and bells marketed under the names saxonette, claribel, and clariphon.