Click Here to hear John Coltrane’s Music

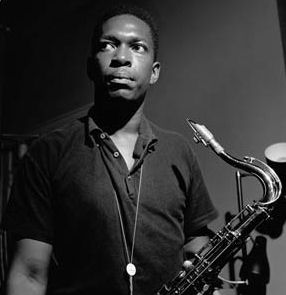

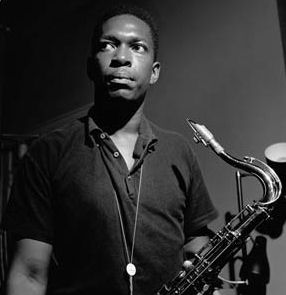

John William Coltrane, also known as “Trane” (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967), was an American jazz saxophonist and composer. Working in the bebop and hard bop idioms early in his career, Coltrane helped pioneer the use of modes in jazz and was later at the forefront of free jazz. He organized at least fifty recording sessions as a leader during his career, and appeared as a sideman on many other albums, notably with trumpeter Miles Davis and pianist Thelonious Monk.

John William Coltrane, also known as “Trane” (September 23, 1926 – July 17, 1967), was an American jazz saxophonist and composer. Working in the bebop and hard bop idioms early in his career, Coltrane helped pioneer the use of modes in jazz and was later at the forefront of free jazz. He organized at least fifty recording sessions as a leader during his career, and appeared as a sideman on many other albums, notably with trumpeter Miles Davis and pianist Thelonious Monk.

As his career progressed, Coltrane and his music took on an increasingly spiritual dimension. His second wife was pianist Alice Coltrane and their son Ravi Coltrane is also a saxophonist. Coltrane influenced innumerable musicians, and remains one of the most significant saxophonists in music history. He received many posthumous awards and recognitions, including canonization by theAfrican Orthodox Church as Saint John William Coltrane and a special Pulitzer Prize in 2007.

Biography

Coltrane’s first recordings were made when he was a sailor.

Saint John William Coltrane

Born September 23, 1926

Hamlet, North Carolina, US

Died July 17, 1967 (aged 40)

Huntington, New York, US

Honored in African Orthodox Church

Information about Coltrane’s canonization

Early life and career (1926–1954)

Coltrane was born in Hamlet, North Carolina on September 23, 1926, and grew up in High Point, North Carolina, attending William Penn High School (now Penn-Griffin School for the Arts). Beginning in December 1938 Coltrane’s aunt, grandparents, and father all died within a few months of each other, leaving John to be raised by his mother and a close cousin.[3] In June 1943 he moved to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. To avoid being drafted by the Army, he enlisted in the Navy on August 6, 1945, the day the first U.S. atomic bomb was dropped on Japan. He was trained as an apprentice seaman at Sampson Naval Training Station in upstate New York before he was shipped to Pearl Harbor, where he was stationed at Manana Barracks, the largest posting of African-American servicemen in the world. By the time he got to Hawaii, in late 1945, the Navy was already rapidly downsizing. Coltrane’s musical talent was quickly recognized, though, and he became one of the few Navy men to serve as a musician without having been granted musicians rating when he joined the Melody Masters, the base swing band. He continued to perform other duties when not playing with the band, including kitchen and security details. By the end of his service, he had assumed a leadership role in the band. After mustering out of the Navy, as a seaman first class in August 1946, he returned to Philadelphia, where he “plunged into the heady excitement of the new music and the blossoming bebop scene.” After touring with King Kolax, he joined a Philly-based band led by Jimmy Heath, who was introduced to Coltrane’s playing by his former Navy buddy, the trumpeter William Massey, who had played with Coltrane in the Melody Masters In Philadelphia after the war, he studied jazz theory with guitarist and composer Dennis Sandole and continued under Sandole’s tutelage through the early 1950s. Originally an altoist, during this time Coltrane also began playing tenor saxophone with the Eddie Vinson Band. Coltrane later referred to this point in his life as a time when “a wider area of listening opened up for me. There were many things that people like Hawk [Coleman Hawkins], and Ben [Webster] , and Tab Smith were doing in the ’40s that I didn’t understand, but that I felt emotionally.”

An important moment in the progression of Coltrane’s musical development occurred on June 5, 1945, when he saw Charlie Parker perform for the first time. In a DownBeat article in 1960 he recalled: “the first time I heard Bird play, it hit me right between the eyes.”Parker became an early idol, and they played together on occasion in the late 1940s.

Contemporary correspondence shows that Coltrane was already known as “Trane” by this point, and that the music from some 1946 recording sessions had been played for trumpeter Miles Davis—possibly impressing him.

There are recordings of Coltrane from as early as 1945. He was a member of groups led by Dizzy Gillespie, Earl Bostic and Johnny Hodges in the early- to mid-1950s.

Miles and Monk period (1955–1957)

The rivalry, tension, and mutual respect between Coltrane and bandleader Miles Davis was formative for both of their careers.

Coltrane was freelancing in Philadelphia in the summer of 1955 while studying with guitarist Dennis Sandole when he received a call from Davis. The trumpeter, whose success during the late forties had been followed by several years of decline in activity and reputation, due in part to his struggles with heroin, was again active and about to form a quintet. Coltrane was with this edition of the Davis band (known as the “First Great Quintet”—along with Red Garland on piano, Paul Chambers on bass, and Philly Joe Jones on drums) from October 1955 to April 1957 (with a few absences), a period during which Davis released several influential recordings which revealed the first signs of Coltrane’s growing ability. This quintet, represented by two marathon recording sessions for Prestige in 1956 that resulted in the albums Cookin’, Relaxin’, Workin’, and Steamin’, disbanded due in part to Coltrane’s heroin addiction.

During the later part of 1957 Coltrane worked with Thelonious Monk at New York’s Five Spot, and played in Monk’s quartet (July–December 1957), but, owing to contractual conflicts, took part in only one official studio recording session with this group. A private recording made by Juanita Naima Coltrane of a 1958 reunion of the group was issued by Blue Note Records in 1993 as Live at the Five Spot-Discovery! A high quality tape of a concert given by this quartet in November 1957 was also found later, and in 2005 Blue Note made it available on CD and LP. Recorded by Voice of America, the performances confirm the group’s reputation, and the resulting album,Thelonious Monk Quartet with John Coltrane at Carnegie Hall, is widely acclaimed.

Blue Train, Coltrane’s sole date as leader for Blue Note, featuring trumpeter Lee Morgan, bassist Paul Chambers, and trombonist Curtis Fuller, is often considered his best album from this period. Four of its five tracks are original Coltrane compositions, and the title track, “Moment’s Notice”, and “Lazy Bird”, have become standards. Both tunes employed the first examples of his chord substitution cycles known as Coltrane changes.

Davis and Coltrane

Coltrane rejoined Davis in January 1958. In October of that year, jazz critic Ira Gitler coined the term “sheets of sound” to describe the style Coltrane developed during his stint with Monk and was perfecting in Davis’ group, now a sextet. His playing was compressed, with rapid runs cascading in hundreds of notes per minute. He stayed with Davis until April 1960, working with alto saxophonist Cannonball Adderley; pianists Red Garland, Bill Evans, and Wynton Kelly; bassist Paul Chambers; and drummers Philly Joe Jones and Jimmy Cobb. During this time he participated in the Davis sessions Milestones and Kind of Blue, and the concert recordings Miles & Monk at Newport and Jazz at the Plaza.

At the end of this period Coltrane recorded his first album for Atlantic Records, Giant Steps, made up exclusively of his own compositions. The album’s title track is generally considered to have the most complex and difficult chord progression of any widely-played jazz composition. Giant Steps utilizes Coltrane changes. His development of these altered chord progression cycles led to further experimentation with improvised melody and harmony that he would continue throughout his career. First albums as leader.

Coltrane formed his first group, a quartet, in 1960 for an appearance at the Jazz Gallery in New York City. After moving through different personnel including Steve Kuhn, Pete La Roca, and Billy Higgins, the lineup stabilized in the fall with pianistMcCoy Tyner, bassist Steve Davis, and drummer Elvin Jones. Tyner, from Philadelphia, had been a friend of Coltrane’s for some years and the two men had an understanding that the pianist would join Coltrane when Tyner felt ready for the exposure of regularly working with him. Also recorded in the same sessions[clarification needed] were the later released albumsColtrane’s Sound and Coltrane Plays the Blues.

Still with Atlantic Records, Coltrane’s first record with his new group was also his debut playing the soprano saxophone, the hugely successful My Favorite Things. Around the end of his tenure with Davis, Coltrane had begun playing soprano, an unconventional move considering the instrument’s near obsolescence in jazz at the time. His interest in the straight saxophone most likely arose from his admiration for Sidney Bechet and the work of his contemporary, Steve Lacy, even though Davis claimed to have given Coltrane his first soprano saxophone. The new soprano sound was coupled with further exploration. For example, on the Gershwin tune “But Not for Me”, Coltrane employs the kinds of restless harmonic movement (Coltrane changes) used on Giant Steps (movement in major thirds rather than conventional perfect fourths) over the A sections instead of a conventional turnaround progression. Several other tracks recorded in the session utilized this harmonic device, including “26–2”, “Satellite”, “Body and Soul”, and “The Night Has a Thousand Eyes”.

First years with Impulse Records (1960–1962)

In May 1961, Coltrane’s contract with Atlantic was bought out by the newly formed Impulse! Records label. An advantage to Coltrane recording with Impulse! was that it would enable him to work again with engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who had taped both his and Davis’ Prestige sessions, as well as Blue Train. It was at Van Gelder’s new studio inEnglewood Cliffs, New Jersey that Coltrane would record most of his records for the label.

By early 1961, bassist Davis had been replaced by Reggie Workman, while Eric Dolphy joined the group as a second horn around the same time. The quintet had a celebrated (and extensively recorded) residency in November 1961 at the Village Vanguard, which demonstrated Coltrane’s new direction. It featured the most experimental music he had played up to this point, influenced by Indian ragas, the recent developments in modal jazz, and the burgeoning free jazz movement. John Gilmore, a longtime saxophonist with musician Sun Ra, was particularly influential; after hearing a Gilmore performance, Coltrane is reported to have said “He’s got it! Gilmore’s got the concept!” The most celebrated of the Vanguard tunes, the 15-minute blues, “Chasin’ the ‘Trane”, was strongly inspired by Gilmore’s music.

During this period, critics were fiercely divided in their estimation of Coltrane, who had radically altered his style. Audiences, too, were perplexed; in France he was booed during his final tour with Davis. In 1961, Down Beat magazine indicted Coltrane and Dolphy as players of “Anti-Jazz”, in an article that bewildered and upset the musicians. Coltrane admitted some of his early solos were based mostly on technical ideas. Furthermore, Dolphy’s angular, voice-like playing earned him a reputation as a figurehead of the “New Thing” (also known as “Free Jazz” and “Avant-Garde”) movement led by Ornette Coleman, which was also denigrated by some jazz musicians (including Davis) and critics. But as Coltrane’s style further developed, he was determined to make each performance “a whole expression of one’s being”.

Classic Quartet period (1962–1965)

ed and Jimmy Garrison replaced Workman as bassist. From then on, the “Classic Quartet”, as it came to be known, with Tyner, Garrison, and Jones, produced searching, spiritually driven work. Coltrane was moving toward a more harmonically static style that allowed him to expand his improvisations rhythmically, melodically, and motivically. Harmonically complex music was still present, but on stage Coltrane heavily favored continually reworking his “standards”: “Impressions”, “My Favorite Things”, and “I Want to Talk About You”.

The criticism of the quintet with Dolphy may have had an impact on Coltrane. In contrast to the radicalism of his 1961 recordings at the Village Vanguard, his studio albums in 1962 and 1963 (with the exception of Coltrane, which featured a blistering version of Harold Arlen’s “Out of This World”) were much more conservative and accessible. He recorded an album of ballads and participated in collaborations with Duke Ellington on the album Duke Ellington and John Coltrane and with deep-voiced ballad singer Johnny Hartman on an eponymous co-credited album. The album Ballads is emblematic of Coltrane’s versatility, as the quartet shed new light on old-fashioned standards such as “It’s Easy to Remember”. Despite a more polished approach in the studio, in concert the quartet continued to balance “standards” and its own more exploratory and challenging music, as can be heard on the Impressions album (two extended jams including the title track along with “Dear Old Stockholm”, “After the Rain” and a blues), Coltrane at Newport(where he plays “My Favorite Things”) and Live at Birdland, both[disambiguation needed] from 1963. Coltrane later said he enjoyed having a “balanced catalogue.”

The Classic Quartet produced their most famous record, A Love Supreme, in December 1964. It is reported that Coltrane, who struggled with repeated drug addiction, derived inspiration for A Love Supreme through a near overdose in 1957 which galvanized him to spirituality. A culmination of much of Coltrane’s work up to this point, this four-part suite is an ode to his faith in and love for God. These spiritual concerns would characterize much of Coltrane’s composing and playing from this point onwards, as can be seen from album titles such as Ascension, Om and Meditations. The fourth movement of A Love Supreme, “Psalm”, is, in fact, a musical setting for an original poem to God written by Coltrane, and printed in the album’s liner notes. Coltrane plays almost exactly one note for each syllable of the poem, and bases his phrasing on the words. Despite its challenging musical content, the album was a commercial success by jazz standards, encapsulating both the internal and external energy of the quartet of Coltrane, Tyner, Jones and Garrison. The album was composed at Coltrane’s home in Dix Hills on Long Island.

The quartet played A Love Supreme live only once—in July 1965 at a concert in Antibes, France. By then, Coltrane’s music had grown even more adventurous, and the performance provides an interesting contrast to the original.

Avant-garde jazz and the second quartet (1965–1967)

As Coltrane’s interest in jazz became increasingly experimental, he added Pharoah Sanders to his ensemble.

In his late period, Coltrane showed an increasing interest in avant-garde jazz, purveyed by Coleman, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra and others. In developing his late style, Coltrane was especially influenced by the dissonance of Ayler’s trio with bassist Gary Peacock and drummer Sunny Murray, a rhythm section honed with Cecil Taylor as leader. Coltrane championed many younger free jazz musicians (notably Archie Shepp), and under his influence Impulse! became a leading free jazz record label.

After A Love Supreme was recorded, Ayler’s style became more prominent in Coltrane’s music. A series of recordings with the Classic Quartet in the first half of 1965 show Coltrane’s playing becoming increasingly abstract, with greater incorporation of devices likemultiphonics, utilization of overtones, and playing in the altissimo register, as well as a mutated return of Coltrane’s sheets of sound. In the studio, he all but abandoned his soprano to concentrate on the tenor saxophone. In addition, the quartet responded to the leader by playing with increasing freedom. The group’s evolution can be traced through the recordings The John Coltrane Quartet Plays, Living Space, Transition (both June 1965), New Thing at Newport (July 1965), Sun Ship (August 1965), and First Meditations (September 1965).

In June 1965, he went into Van Gelder’s studio with ten other musicians (including Shepp, Pharoah Sanders, Freddie Hubbard, Marion Brown, and John Tchicai) to record Ascension, a 40-minute piece that included solos by the young avant-garde musicians (as well as Coltrane), and was controversial primarily for the collective improvisation sections that separated the solos. After recording with the quartet over the next few months, Coltrane invited Sanders to join the band in September 1965. While Coltrane used over-blowing frequently as an emotional exclamation-point, Sanders would overblow his entire solo, resulting in a constant screaming and screeching in the altissimo range of the instrument.

Adding to the quartet

Percussionist Rashied Ali helped to augment Coltrane’s sound in the last years of his life.

By late 1965, Coltrane was regularly augmenting his group with Sanders and other free jazz musicians. Rashied Ali joined the group as a second drummer. This was the end of the quartet; claiming he was unable to hear himself over the two drummers, Tyner left the band shortly after the recording of Meditations. Jones left in early 1966, dissatisfied by sharing drumming duties with Ali. Both Tyner and Jones subsequently expressed displeasure in interviews, after Coltrane’s death, with the music’s new direction, while incorporating some of the free-jazz form’s intensity into their own solo projects.

There is speculation that in 1965 Coltrane began using LSD, informing the “cosmic” transcendence of his late period. After the departure of Jones and Tyner, Coltrane led a quintet with Sanders on tenor saxophone, his second wife Alice Coltrane on piano, Garrison on bass, and Ali on drums. Coltrane and Sanders were described by Nat Hentoff as “speaking in tongues”. When touring, the group was known for playing very lengthy versions of their repertoire, many stretching beyond 30 minutes and sometimes being an hour long. Concert solos for band members often extended beyond fifteen minutes.

The group can be heard on several concert recordings from 1966, including Live at the Village Vanguard Again! and Live in Japan. In 1967, Coltrane entered the studio several times; though pieces with Sanders have surfaced (the unusual “To Be”, which features both men on flutes), most of the recordings were either with the quartet minus Sanders (Expression and Stellar Regions) or as a duo with Ali. The latter duo produced six performances that appear on the album Interstellar Space.

Death and funeral

Coltrane died from liver cancer at Huntington Hospital on Long Island on July 17, 1967, at the age of 40. His funeral was held four days later at St. Peter’s Lutheran Church in New York City. The service was opened by the Albert Ayler Quartet and closed by the Ornette Coleman Quartet. Coltrane is buried at Pinelawn Cemetery in Farmingdale, New York.

The biographer Lewis Porter has suggested that the cause of Coltrane’s illness was hepatitis, although he also attributed the disease to Coltrane’s heroin use. In a 1968 interview Ayler claimed that Coltrane was consulting a Hindu meditative healer for his illness instead of Western medicine, although Alice Coltrane later denied this.

Coltrane’s death surprised many in the musical community who were not aware of his condition. Davis said that “Coltrane’s death shocked everyone, took everyone by surprise. I knew he hadn’t looked too good… But I didn’t know he was that sick—or even sick at all.”

Personal life and religious beliefs

Coltrane’s second wife, Alice, performed with him and also challenged his spiritual beliefs.

In 1955, Coltrane married Juanita Naima Grubbs, a Muslim convert, for whom he later wrote the piece “Naima”, and came into contact with Islam. They had no children together and were separated by the middle of 1963. Not long after that, Coltrane met pianist Alice McLeod. He and Alice moved in together and had two sons before he was “officially divorced from Naima in 1966, at which time John and Alice were immediately married.” John Jr. was born in 1964, Ravi in 1965, and Oranyan (“Oran”) in 1967. According to the musician and author Peter Lavezzoli, “Alice brought happiness and stability to John’s life, not only because they had children, but also because they shared many of the same spiritual beliefs, particularly a mutual interest in Indian philosophy. Alice also understood what it was like to be a professional musician.”

Coltrane was born and raised in a Christian home, and was influenced by religion and spirituality from childhood. His maternal grandfather, the Reverend William Blair, was a minister at an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in High Point, North Carolina, and his paternal grandfather, the Reverend William H. Coltrane, was an A.M.E. Zion minister in Hamlet, North Carolina.Critic Norman Weinstein noted the parallel between Coltrane’s music and his experience in the southern church, which included practicing music there as a youth.

In 1957, Coltrane had a religious experience which may have led him to overcome the heroin addiction and alcoholism he had struggled with since 1948. In the liner notes of A Love Supreme, Coltrane states that, in 1957, “I experienced, by the grace of God, a spiritual awakening which was to lead me to a richer, fuller, more productive life. At that time, in gratitude, I humbly asked to be given the means and privilege to make others happy through music.” The liner notes appear to mention God in a Universalist sense, and do not advocate one religion over another. Further evidence of this universal view regarding spirituality can be found in the liner notes of Meditations (1965), in which Coltrane declares, “I believe in all religions.”

After A Love Supreme, many of the titles of Coltrane’s songs and albums were linked to spiritual matters: Ascension, Meditations, Om, Selflessness, “Amen”, “Ascent”, “Attaining”, “Dear Lord”, “Prayer and Meditation Suite”, and “The Father and the Son and the Holy Ghost”. Coltrane’s collection of books included The Gospel of Sri Ramakrishna, the Bhagavad Gita, and Paramahansa Yogananda’s Autobiography of a Yogi. The last of these describes, in Lavezzoli’s words, a “search for universal truth, a journey that Coltrane had also undertaken. Yogananda believed that both Eastern and Western spiritual paths were efficacious, and wrote of the similarities between Krishna and Christ. This openness to different traditions resonated with Coltrane, who studied the Qur’an, the Bible, Kabbalah, and astrology with equal sincerity.” He also explored Hinduism, Jiddu Krishnamurti, African history, the philosophical teachings of Plato and Aristotle, and Zen Buddhism.

In October 1965, Coltrane recorded Om, referring to the sacred syllable in Hinduism which symbolizes the infinite or the entire Universe. Coltrane described Om as the “first syllable, the primal word, the word of power”. The 29-minute recording contains chants from the Hindu Bhagavad Gita and the Buddhist Tibetan Book of the Dead, and a recitation of a passage describing the primal verbalization “om” as a cosmic/spiritual common denominator in all things.

Coltrane’s spiritual journey was interwoven with his investigation of world music. He believed not only in a universal musical structure which transcended ethnic distinctions, but in being able to harness the mystical language of music itself. Coltrane’s study of Indian music led him to believe that certain sounds and scales could “produce specific emotionalmeanings.” According to Coltrane, the goal of a musician was to understand these forces, control them, and elicit a response from the audience. Coltrane said: “I would like to bring to people something like happiness. I would like to discover a method so that if I want it to rain, it will start right away to rain. If one of my friends is ill, I’d like to play a certain song and he will be cured; when he’d be broke, I’d bring out a different song and immediately he’d receive all the money he needed.”

Religious figure

Coltrane icon at St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church

After Coltrane’s death, a congregation called the Yardbird Temple in San Francisco began worshipping him as God incarnate. The group was named after Parker, whom they equated to John the Baptist. The congregation later became affiliated with the African Orthodox Church; this involved changing Coltrane’s status from a god to a saint. The resultant St. John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, San Francisco is the only African Orthodox church that incorporates Coltrane’s music and his lyrics as prayers in its liturgy.

Samuel G. Freedman wrote in a New York Times article that “the Coltrane church is not a gimmick or a forced alloy of nightclub music and ethereal faith. Its message of deliverance through divine sound is actually quite consistent with Coltrane’s own experience and message.”Freedman also commented on Coltrane’s place in the canon of American music:

In both implicit and explicit ways, Coltrane also functioned as a religious figure. Addicted to heroin in the 1950s, he quit cold turkey, and later explained that he had heard the voice of God during his anguishing withdrawal. […] In 1966, an interviewer in Japan asked Coltrane what he hoped to be in five years, and Coltrane replied, “A saint.”

Coltrane is depicted as one of the 90 saints in the Dancing Saints icon of St. Gregory of Nyssa Episcopal Church in San Francisco. The icon is a 3,000-square-foot (280 m2) painting in the Byzantine iconographic style that wraps around the entire church rotunda. It was executed by Mark Dukes, an ordained deacon at the Saint John Coltrane African Orthodox Church, who painted other icons of Coltrane for the Coltrane Church. Saint Barnabas Episcopal Church in Newark, New Jersey included Coltrane on their list of historical black saints and made a “case for sainthood” for him in an article on their former website.

Documentaries on Coltrane and the church include Alan Klingenstein’s The Church of Saint Coltrane (1996), and a 2004 program presented by Alan Yentob for theBBC.

Instruments

Coltrane played the clarinet and the alto horn in a community band before taking up the alto saxophone during high school. In 1947, when he joined King Kolax’s band, Coltrane switched to tenor saxophone, the instrument he became known for playing primarily. Coltrane’s preference for playing melody higher on the range of the tenor saxophone (as compared to, for example, Coleman Hawkins or Lester Young) is attributed to his start and training on the alto horn and clarinet; his “sound concept” (manipulated in one’s vocal tract—tongue, throat) of the tenor was set higher than the normal range of the instrument.

In the early 1960s, during his engagement with Atlantic Records, he increasingly played soprano saxophone as well. Toward the end of his career, he experimented with flute in his live performances and studio recordings (Live at the Village Vanguard Again!, Expression). Dolphy’s mother is reported to have given Coltrane his flute and bass clarinet after Dolphy’s death in 1964.

Coltrane’s tenor (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 125571, dated 1965) and soprano (Selmer Mark VI, serial number 99626, dated 1962) saxophones were auctioned on February 20, 2005 to raise money for the John Coltrane Foundation. The soprano raised $70,800 but the tenor remained unsold.

Legacy

John Coltrane House, 1511 North Thirty-third Street, Philadelphia

The influence Coltrane has had on music spans many genres and musicians. Coltrane’s massive influence on jazz, both mainstream and avant-garde, began during his lifetime and continued to grow after his death. He is one of the most dominant influences on post-1960 jazz saxophonists and has inspired an entire generation of jazz musicians.

In 1965, Coltrane was inducted into the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame. In 1972, A Love Supreme was certified gold by the RIAA for selling over half a million copies in Japan. This album, as well as My Favorite Things, was certified gold in the United States in 2001. In 1982 he was awarded a posthumous Grammy for “Best Jazz Solo Performance” on the album Bye Bye Blackbird, and in 1997 he was awarded theGrammy Lifetime Achievement Award. In 2002, scholar Molefi Kete Asante named Coltrane one of his 100 Greatest African Americans. Coltrane was awarded a special Pulitzer Prize in 2007 citing his “masterful improvisation, supreme musicianship and iconic centrality to the history of jazz.” He was inducted into the North Carolina Music Hall of Fame in 2009.

His widow, Alice Coltrane, after several decades of seclusion, briefly regained a public profile before her death in 2007. A former home, the John Coltrane House in Philadelphia, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1999. His last home, the John Coltrane Home in the Dix Hills district of Huntington, New York, where he resided from 1964 until his death, was added to the National Register of Historic Places on June 29, 2007. One of their sons, Ravi Coltrane, named after the sitarist Ravi Shankar, is also a saxophonist.

The Coltrane family reportedly possesses much more unreleased music, mostly mono reference tapes made for the saxophonist, and, as with the 1995 release Stellar Regions, master tapes that were checked out of the studio and never returned.[citation needed] The parent company of Impulse!, from 1965 to 1979 known as ABC Records, purged much of its unreleased material in the 1970s. Lewis Porter has stated that Alice Coltrane intended to release this music, but over a long period of time; Ravi Coltrane is responsible for reviewing the material.[citation needed]

Discography

Main article: John Coltrane discography

The discography below lists albums conceived and approved by Coltrane as a leader during his lifetime. It does not include his many releases as a sideman, sessions assembled into albums by various record labels after Coltrane’s contract expired, sessions with Coltrane as a sideman later reissued with his name featured more prominently, or posthumous compilations except for the one which he approved before his death. See main discography link above for full list.

Prestige and Blue Note Records

Coltrane (debut solo LP) (1957)

Blue Train (1957)

John Coltrane with the Red Garland Trio (1958)

Soultrane (1958)

Atlantic Records

Giant Steps (first album entirely of Coltrane compositions) (1960)

Coltrane Jazz (first appearance by McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones) (1961)

My Favorite Things (1961)

Olé Coltrane (features Eric Dolphy, compositions by Coltrane and Tyner) (1961)

Impulse! Records

Africa/Brass (brass arranged by Tyner and Dolphy) (1961)

Live! at the Village Vanguard (features Dolphy, first appearance by Jimmy Garrison) (1962)

Coltrane (first album to solely feature the “classic quartet”) (1962)

Ballads (1963)

John Coltrane and Johnny Hartman (1963)

Impressions (1963)

Duke Ellington & John Coltrane (1964)

Live at Birdland (1964)

Crescent (1964)

A Love Supreme (1965)

The John Coltrane Quartet Plays (1965)

Ascension (1966)

New Thing at Newport (live with Archie Shepp) (1966)

Kulu Sé Mama (1966)

Meditations (quartet plus Pharoah Sanders and Rashied Ali) (1966)

Expression (posthumous and final Coltrane-approved release; one track features Coltrane on flute) (1967)